Biologic drugs like Humira, Enbrel, and Remicade have changed how we treat autoimmune diseases, cancer, and other serious conditions. But they come with a price tag-often over $100,000 a year. That’s why biosimilars matter. They’re not copies like generic pills, but highly similar versions of these complex medicines. And when they finally hit the market, they can slash costs by 30% to 80%. But getting them there isn’t simple. It’s not just about waiting for a patent to expire. It’s a 12-year legal and regulatory marathon designed to protect drugmakers-and delay competition.

Why Biosimilars Aren’t Like Generic Pills

You’ve probably taken a generic version of a drug like lisinopril or metformin. They’re chemically identical to the brand name, made with simple molecules, and cost pennies. Biosimilars? They’re different. Biologics are made from living cells-think proteins, antibodies, or engineered cells. Their structure is so complex that even tiny changes in manufacturing can affect how they work. That’s why the FDA doesn’t call them "generics." They must prove they’re "highly similar" with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. That takes years of testing, billions of dollars, and advanced labs most companies can’t afford.Developing a biosimilar can cost $100 million to $250 million and take five to ten years. Compare that to a small-molecule generic, which might cost $2 million and take two years. That’s why only 38 biosimilars have been approved in the U.S. since 2015, while Europe has approved 88. The gap isn’t just about regulation-it’s about money, risk, and legal barriers.

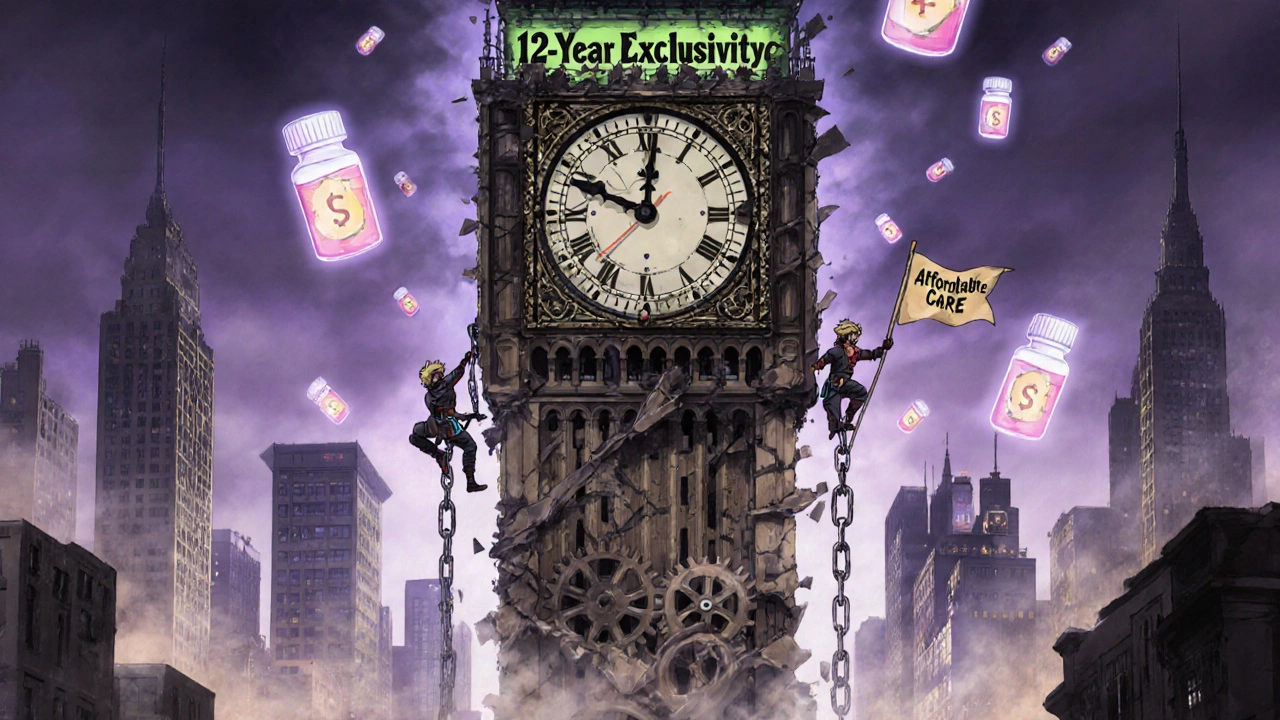

The 12-Year Exclusivity Clock

The U.S. system is built around the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009. This law gives innovator companies two layers of protection. First, a 4-year data exclusivity period: no one can even submit a biosimilar application to the FDA until four years after the original drug gets approved. Then comes the 12-year market exclusivity: even if a biosimilar application is filed after year four, the FDA can’t approve it until 12 years have passed.This means a drug like Humira, approved in 2002, couldn’t face biosimilar competition until 2018 at the earliest. But it didn’t happen until 2023-because of patents, not just exclusivity. That’s the real trick: exclusivity gives you a legal wall. Patents build a maze around it.

The Patent Dance: A Legal Trapdoor

After a biosimilar applicant submits its application, the law requires something called the "patent dance." It sounds like a formal handshake. In reality, it’s a high-stakes negotiation that often turns into a lawsuit.Here’s how it works: the biosimilar maker sends its full application and manufacturing details to the original drug company. That company then picks which patents it thinks are being infringed. The biosimilar maker responds, often denying infringement or claiming the patents are invalid. Then both sides meet to pick which patents to litigate immediately. Most of the time, they don’t agree. So lawsuits begin.

AbbVie, the maker of Humira, filed over 160 patents on the drug-even though its core patent expired in 2016. By the time the first biosimilar was approved in 2023, 13 separate lawsuits had been filed. Each delay added months, sometimes years, to the timeline. This isn’t rare. According to Duke University’s Professor Arti Rai, 87% of biosimilar cases involve multiple patent claims. The system was meant to resolve disputes quickly. Instead, it’s become a tool for dragging out competition.

Global Differences: Why Europe Got Biosimilars Sooner

In Europe, biologics get 10 years of data exclusivity and one year of market exclusivity-11 total. The process is simpler. No patent dance. Fewer lawsuits. And once approved, doctors and pharmacies are encouraged to switch to biosimilars. As a result, biosimilars now make up 72% of the market for drugs with competition.In the U.S., the same drugs didn’t see biosimilars for years. Humira was available in Europe in 2018. In the U.S., it took until 2023. During those five years, U.S. patients paid over $167 billion more than Europeans for the same treatment. That’s not just a pricing difference-it’s a policy failure.

Japan and South Korea have their own timelines, but none are as long as the U.S. The 12-year exclusivity period is among the longest in the world. And it’s not based on science. It’s political. The biotech industry lobbied hard for it. Groups like the Biotechnology Innovation Organization argue it’s necessary to fund innovation. But critics-like AARP, Doctors Without Borders, and patient advocates-say it’s a money grab that keeps life-saving drugs out of reach.

The Biosimilar Void: What’s Not Coming

Here’s the scary part: even as big-name biologics start losing protection, many won’t see biosimilars at all. Between 2025 and 2034, 118 biologics will lose patent protection worth $234 billion. But only 12 have biosimilars in development.Why? Three big reasons:

- Orphan drugs: 64% of expiring biologics treat rare diseases. No company wants to spend $200 million on a drug used by only 5,000 people.

- Complex molecules: Antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and gene therapies are too hard to replicate. None currently have biosimilars in the pipeline, even though 16 will lose patent protection by 2034.

- Poor ROI: If a drug’s sales are falling, or it’s already off-patent in Europe, companies don’t see the return.

Take eculizumab, a rare disease drug. Only one biosimilar is in development. For 88% of expiring orphan biologics? Nothing. That’s not innovation-it’s abandonment. Patients with rare conditions could be left without affordable options for decades.

Who’s Losing? Patients, Pharmacies, and the System

The cost isn’t just financial. It’s personal. A 2022 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found 63% of pharmacists had patients who stopped taking their biologic because they couldn’t afford it. The Arthritis Foundation documented cases where Humira’s price jumped 470% between 2012 and 2022 while European prices stayed flat after biosimilars arrived.Doctors like Dr. Peter Bach at Memorial Sloan Kettering say U.S. patients pay three times more for the same drugs. That’s not just unfair-it’s dangerous. When people skip doses or quit treatment because of cost, their health suffers. Hospital visits go up. Long-term outcomes get worse.

And it’s not just patients. Pharmacies, insurers, and Medicare all pay more. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that if biosimilars entered the market faster, the U.S. could save $158 billion over the next decade. Under current rules? Only $71 billion.

What’s Changing? Not Much

The FDA’s 2022 Biosimilars Action Plan promised to improve communication, speed up approvals, and support competition. But progress is slow. Only 38 biosimilars approved in 10 years. The Biosimilars User Fee Act of 2022, meant to streamline the process, died in committee. No major legislation has passed since.Meanwhile, the clock keeps ticking. Over 100 biologics are set to lose protection by 2034. If nothing changes, most will remain expensive. Patients will keep paying more. And the system will keep bleeding money.

There’s no magic fix. But there are clear steps: shorten exclusivity, ban patent thickets, fund development for orphan drugs, and require insurers to favor biosimilars. Without those changes, the U.S. will keep lagging behind the rest of the world-not because of science, but because of policy.

How long do biologic patents last before biosimilars can enter the U.S.?

Under U.S. law, biosimilars can’t be approved until 12 years after the original biologic drug received FDA approval. Even before that, manufacturers can’t submit their application until 4 years after approval. This 12-year exclusivity period is set by the BPCIA of 2009 and can be extended by six months if the drug company completes pediatric studies.

Why are biosimilars more expensive to develop than generic drugs?

Biologics are made from living cells, not chemicals, so their structure is far more complex. Replicating them requires advanced manufacturing, years of testing, and costly clinical trials to prove they’re "highly similar" with no clinically meaningful differences. Developing a biosimilar can cost $100 million to $250 million and take 5-10 years. Generic small-molecule drugs cost $1-2 million and take about 2 years.

What is the "patent dance" and how does it delay biosimilars?

The "patent dance" is a legal process under the BPCIA where a biosimilar applicant shares its application with the original drug maker, who then lists patents it believes are being infringed. The biosimilar maker responds, and both sides negotiate which patents to litigate. In practice, this often leads to multiple lawsuits, with companies like AbbVie filing over 160 patents on Humira to delay competition. The process can add years to the timeline, even after exclusivity ends.

Why do biosimilars enter the market earlier in Europe than in the U.S.?

Europe offers 10 years of data exclusivity and 1 year of market exclusivity-11 years total-compared to the U.S.’s 12. Europe also lacks the complex "patent dance," has stronger incentives for biosimilar use, and regulators actively encourage switching. As a result, biosimilars make up 72% of the market for competing biologics in Europe, while the U.S. lags far behind.

Are there any biologics that won’t ever have biosimilars?

Yes. Many biologics with orphan drug status (used for rare diseases) or highly complex structures like antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and gene therapies have no biosimilars in development. Of the 118 biologics set to lose patent protection between 2025 and 2034, 88% of those with orphan indications have no biosimilar in the pipeline. The high cost and low patient numbers make them unattractive for manufacturers.

What can be done to speed up biosimilar access in the U.S.?

Shortening the exclusivity period, banning patent thickets, creating funding incentives for orphan drug biosimilars, requiring insurers to cover biosimilars first, and simplifying the approval process could all help. Legislative action is needed-current efforts like the Biosimilars User Fee Act stalled in Congress. Without change, patients will continue paying far more than necessary for life-saving treatments.

Comments

This system is rigged.

lol u think this is about science? nah. it's about who owns the patents. big pharma bought the whole congress. 12 years? more like 20 with all their patent trolling. they file patents on the color of the pill. i swear they're writing patents in cursive now. #pharmabrainwashing

India knows this pain. We make generics for the world but here? They treat biology like a sacred text you can't touch. We grow rice in fields, they grow medicine in clean rooms - and then charge you rent for breathing. It's not innovation. It's feudalism with a FDA stamp.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act was designed with precision to balance innovation incentives against market access. The 12-year exclusivity window is not arbitrary; it reflects the substantial capital investment and risk inherent in biologics development. To reduce this period would undermine the very foundation of pharmaceutical R&D, which has delivered life-saving therapies for millions.

Hey, I get it - it’s frustrating. But change is coming. More people are speaking up, more lawmakers are listening. It’s slow, yeah, but every biosimilar approved is a crack in the wall. Keep pushing. Your voice matters. We’re not done yet.

so like… biosimilars are like… knockoff yeezys but for cancer drugs? lol why is this so hard. they just copy the formula right? why spend 100 mill? also why does humira cost more than my car

Europe lets foreign companies undercut American innovation? That’s not free trade - that’s economic surrender. We built this industry with American ingenuity, and now we’re being punished for it. The patent dance isn’t a trap - it’s a defense mechanism. If you want cheap drugs, move to China.

There’s a structural asymmetry in the regulatory architecture here: the BPCIA’s patent dance mechanism, while ostensibly designed for efficiency, has become a strategic litigation vector. The absence of a harmonized global framework exacerbates market fragmentation - particularly in orphan indications where economies of scale are nonviable. The solution lies in tiered exclusivity models coupled with public-private R&D consortia.

It’s not just the patents… it’s the silence. The way doctors don’t even mention biosimilars. The way pharmacies don’t substitute. The way insurance companies make you jump through hoops to get a cheaper version… even when it’s approved. They don’t want you to know it exists. And if you don’t know it exists… you don’t ask for it. And if you don’t ask… they don’t have to give it to you. And the cycle keeps spinning. And people die quietly.

Let me just say this - the whole biosimilar narrative is a distraction. The real problem is that American healthcare is a for-profit death spiral. We’re not talking about science here. We’re talking about CEOs who make 500x what their workers make while patients ration insulin. The 12-year rule? That’s just the tip of the iceberg. The real villain isn’t AbbVie - it’s the entire capitalist model that treats medicine like a luxury good. You want change? Burn the system down. Start over. Or keep paying $100K for a drug that should cost $5K. Your choice.

Thank you for sharing this. Important context.

I’ve seen patients cry because they can’t afford their meds. I’ve seen them skip doses. I’ve seen them choose between insulin and groceries. This isn’t policy. This is cruelty dressed up as law.

So let me get this straight - we spend 12 years making sure no one can make a cheaper version of a drug that costs more than a Tesla… and then we wonder why people can’t afford to live? 😂

There are people out there who need these drugs. Not just in the U.S. - in rural India, in small-town Kenya, in villages where no one has heard of Humira but they’ve heard of death. We can do better. We have to.

Did you know the FDA’s own data shows that 94% of biosimilar applications are submitted after the 12-year mark - meaning the exclusivity period isn’t just a delay, it’s a wall. And the patent dance? It’s not a dance. It’s a hostage situation. AbbVie filed patents on Humira’s packaging, its shipping temperature, the angle of the needle. One patent was for "a method of administering the drug while sitting down." This isn’t innovation. It’s legal terrorism. And Congress lets it happen because they take Big Pharma’s money. The same money that funds their re-elections. The same money that keeps you paying $100K a year. Wake up. This isn’t a glitch. It’s the system working exactly as intended.

My cousin in Delhi got her rheumatoid arthritis meds for $200 a year. Here? Her brother pays $120K. Same drug. Same molecule. Different continent. Different life. We call this progress? This is colonialism with a white coat. They patent life. And we pay for the privilege to breathe. I’ve seen kids in Mumbai with IV bags made of plastic tape because the real ones cost too much. And here? We’re debating whether to shorten exclusivity by six months. This isn’t a debate. It’s a moral emergency. And we’re all just scrolling.