Many people think they’re allergic to penicillin because they had a rash or stomach upset as a kid. But here’s the truth: up to 90% of those who say they’re allergic to penicillin aren’t. That’s not a guess-it’s backed by data from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Most of these labels stick because no one ever tested them properly. And that’s a problem. It leads to doctors prescribing stronger, costlier antibiotics, which increases the risk of resistant infections and drives up hospital bills by around $500 per admission.

What Really Counts as a Drug Allergy?

A true drug allergy is an immune system reaction. It’s not just nausea or a headache. It’s your body treating the medicine like a dangerous invader. The most serious reactions happen within an hour-symptoms like hives, swelling of the face or throat, trouble breathing, or a sudden drop in blood pressure. These are signs of anaphylaxis, and they need emergency care.

Penicillin and related antibiotics (like amoxicillin or cefazolin) are the most common triggers. But NSAIDs-think ibuprofen, naproxen, or aspirin-are close behind. People often don’t realize these painkillers can cause allergic reactions too. For some, it’s just a rash. For others, it’s asthma flare-ups or anaphylaxis, especially if they’ve had reactions before.

Here’s the catch: not every bad reaction is an allergy. A stomach ache after taking an antibiotic? That’s usually a side effect, not an immune response. A rash from amoxicillin in a child with mono? That’s common and not allergic. But without proper testing, doctors play it safe-and overprescribe.

Testing for Penicillin Allergy: Skin Tests and Challenges

If you think you’re allergic to penicillin, the first step isn’t avoiding it forever. It’s getting tested. The gold standard starts with skin testing using penicillin derivatives like PPL and MDM. These are tiny amounts injected under the skin. If there’s a red, itchy bump, it suggests IgE-mediated allergy.

But here’s where things get tricky: up to 70% of people who test positive to PPL alone don’t react to actual penicillin. That’s why experts now say PPL alone shouldn’t be used. A negative skin test is followed by a drug challenge-giving a full dose of amoxicillin under supervision. If no reaction occurs, the allergy label is removed.

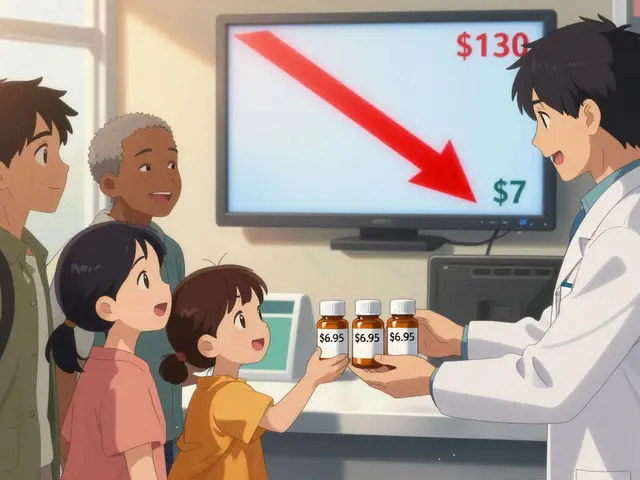

And yes, this is safe when done right. In fact, hospitals across the U.S. and Australia have made this routine. At major centers like Brigham and Women’s, thousands of patients have been cleared without incident. The result? They can go back to using penicillin, which is often the best, cheapest, and safest option for infections like strep throat, pneumonia, or Lyme disease.

NSAID Allergies: A Different Kind of Reaction

NSAID allergies work differently than penicillin ones. They’re rarely IgE-mediated. Instead, they often involve the body’s inflammatory pathways. People with asthma or nasal polyps are especially prone. Taking ibuprofen might trigger wheezing, swelling, or even anaphylaxis-even if they’ve taken it before without issue.

Testing for NSAID allergies isn’t as straightforward as skin tests. There’s no reliable blood or skin test yet. Diagnosis usually comes from a detailed history and, sometimes, an oral challenge under medical supervision. That means slowly increasing the dose of aspirin or another NSAID while watching for symptoms.

For those who truly can’t tolerate NSAIDs, there’s a workaround: desensitization. Unlike penicillin, where tolerance fades after treatment ends, NSAID desensitization can be maintained with daily low doses. Some patients with chronic pain or arthritis take a daily low-dose aspirin to prevent reactions while still getting the anti-inflammatory benefit. It’s not a cure-but it’s a way to live with the condition.

Desensitization Protocols: How They Work

Desensitization isn’t magic. It’s science. The idea is simple: if your immune system overreacts to a drug, you give it tiny, controlled doses-slowly increasing until your body stops seeing it as a threat. This doesn’t fix the allergy. It just puts it to sleep-for one course of treatment.

The most common method is the 12-step protocol. It starts with a dose that’s one ten-thousandth of the full amount. Every 15 to 20 minutes, the dose doubles. The whole process takes 4 to 8 hours. For some antibiotics, like ceftriaxone, a faster version works in just over two hours. Doses are given IV, but sometimes orally if the patient can tolerate it.

Each step is watched closely. Nurses monitor blood pressure, oxygen levels, and breathing. Epinephrine and other emergency meds are always on standby. If a patient gets severe hypotension or throat swelling that doesn’t respond to treatment, the process stops immediately.

Successful desensitization has been done for dozens of drugs: penicillin, nafcillin, cephalosporins, vancomycin, chemotherapy agents like paclitaxel, and even antifungals like fluconazole. It’s not just for infections. It’s critical for cancer patients who need specific chemo drugs, or for someone with a life-threatening infection who has no other options.

Who Gets Desensitized-and Who Doesn’t

Desensitization isn’t for everyone. There are strict rules. First, you must have a confirmed immediate-type reaction. Second, there must be no safe alternative. If you’re allergic to penicillin but can use doxycycline for a sinus infection? Skip desensitization. But if you’re allergic to penicillin and have endocarditis? You need it.

It’s also not a one-time fix. Once the treatment ends, the tolerance disappears. The next time you need that drug, you’ll need to go through the whole process again. That’s why it’s only used when absolutely necessary.

Children are a growing focus. Most protocols were designed for adults. But kids with cancer, cystic fibrosis, or severe infections need these drugs too. Pediatric allergists are now teaming up with oncologists and infectious disease specialists to make desensitization safer and more accessible for younger patients.

Why This Matters Beyond the Clinic

Every time someone is mislabeled as penicillin-allergic, it ripples through the healthcare system. Broader-spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin or carbapenems get used more often. These drugs are more expensive. They’re harder on the gut microbiome. And they contribute to antibiotic resistance-a global health crisis.

Clearing a false penicillin allergy isn’t just good for the patient. It’s good for public health. Hospitals that run allergy clinics report fewer ICU admissions, shorter stays, and lower costs. In Australia, where penicillin remains a first-line treatment for many infections, these programs are expanding slowly but steadily.

Still, access is uneven. Not every hospital has an allergy specialist on staff. Not every GP knows to refer. And many patients don’t even know they can get tested. If you’ve been told you’re allergic to penicillin-or any drug-ask: Was this confirmed? If not, you might be avoiding a safe, effective treatment for no reason.

What to Do If You Think You Have a Drug Allergy

If you’ve had a reaction to a drug, don’t assume it’s an allergy. Write down what happened: when, what drug, what symptoms, how long it lasted. Did you get hives? Trouble breathing? Swelling? Or just a rash or upset stomach?

Then talk to your doctor. Ask if you should be referred to an allergist. Most public hospitals and large private clinics offer drug allergy clinics. The process is usually covered by insurance or Medicare in Australia.

If you’ve been avoiding penicillin or NSAIDs for years, it’s not too late. Getting tested could mean simpler, cheaper, and safer treatment the next time you’re sick.

Desensitization isn’t a last resort. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it works best in the right hands.

Comments

Most people don’t realize how many meds they’re avoiding for no reason. I was labeled penicillin-allergic at 7 because of a rash. Turned out it was mono. Never got tested. Now I’m 34 and still saying no to antibiotics like they’re poison. Maybe I should fix that.

Oh wow, another ‘trust the system’ pamphlet. Next they’ll tell us vaccines are safe and fluoride doesn’t turn you into a mindless drone. Funny how the same institutions that got the opioid crisis wrong are now the ones telling us what’s ‘really’ an allergy.

In Nigeria we don’t have time for all this testing. If you get sick and penicillin works, you take it. If you die, you die. But if you live, you live. Why waste hours on skin tests when the whole village needs medicine? This is rich country luxury. We don’t have allergists. We have faith and antibiotics bought from the market.

Desensitization protocols are a brilliant example of immunological precision engineering. The 12-step incremental dosing paradigm exploits T-cell anergy and IgE receptor downregulation to induce transient tolerance without permanent immune reprogramming. It’s elegant. And yet, primary care providers still default to broad-spectrum empiric therapy because they’re not trained in immunopharmacology. Systemic failure.

They’re pushing this to get us hooked on Big Pharma’s new ‘safe’ antibiotics. Watch how soon after they clear your penicillin label, they start pushing that $800 new version. This isn’t medicine-it’s a revenue model disguised as science. They want you dependent on their drugs, not cured.

There’s a deeper metaphysical truth here: we treat medicine like a religion. We worship the label-‘allergy’-as if it’s a sacred truth carved in stone. But the body is fluid, the immune system a living poem, not a fixed contract. To cling to a childhood rash as dogma is to mistake the map for the territory. We’ve forgotten that healing is not about avoiding danger, but understanding its dance.

So… if I had a rash as a kid, I’m probably not allergic? 🤯

This is actually super helpful. I’ve been avoiding ibuprofen for years because I got a rash once. Guess I should talk to my doctor. Thanks for breaking it down like this 😊

I love how this post doesn’t just scare people-it gives real steps. So many health posts just say ‘you’re probably fine’ and leave you hanging. This says: here’s what to do next. Thank you for being practical.

Consider the implications. The medical establishment has spent decades propagating a myth of penicillin allergy-rooted in misdiagnosis, fear, and institutional inertia. And now, in the age of antibiotic resistance, we are forced to confront the consequences of collective cognitive dissonance. The patient, once the passive recipient of diagnosis, must now become an active interrogator of their own medical history. This is not just clinical-it is existential. We are not merely treating infections. We are dismantling the mythologies of modern medicine, one skin test at a time.

Wait-so if I had a rash after amoxicillin as a kid, and I had mono at the time, that’s not an allergy? And if I’ve never had hives, swelling, or breathing issues since? Then it’s not an allergy? And if I get tested and cleared, I can use penicillin again? And this is actually standard in Australia and major U.S. hospitals? And it’s covered by insurance? Why didn’t anyone tell me this before? I’ve been avoiding penicillin for 20 years because a 10-year-old doctor said ‘better safe than sorry.’