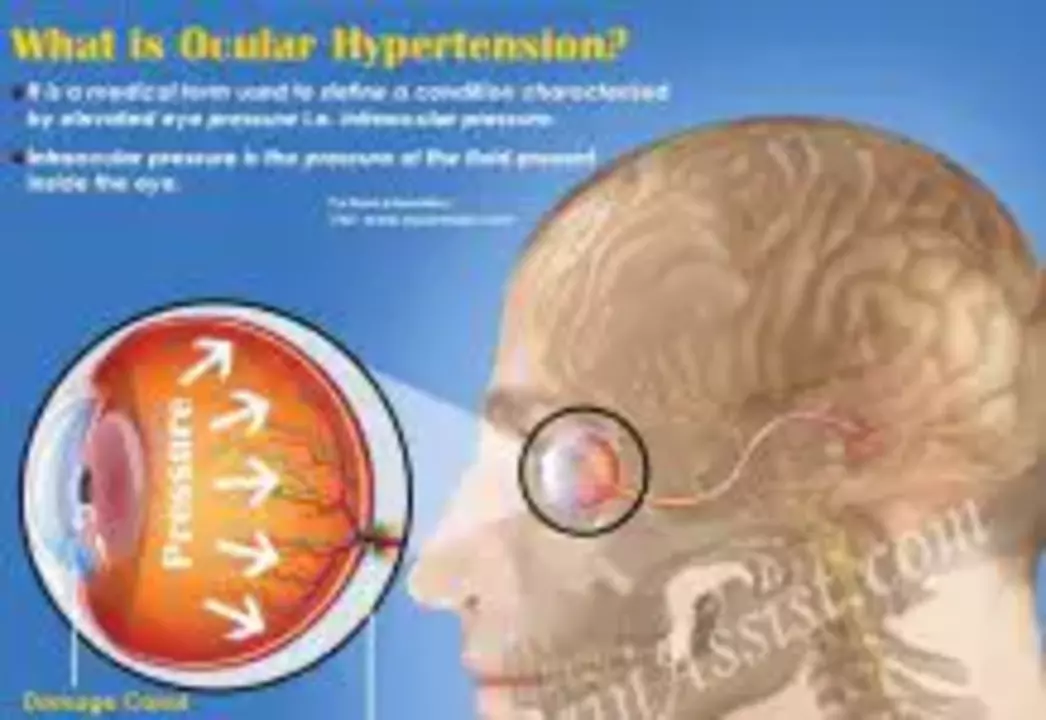

Ocular Hypertension — What It Is and Why It Matters

Ocular hypertension means your eye pressure (intraocular pressure or IOP) is higher than normal—usually over 21 mmHg—without clear signs of glaucoma damage. High pressure alone doesn’t always cause vision loss, but it raises the chance of developing glaucoma. If you’ve been told you have ocular hypertension, understanding tests, risk factors, and treatment choices can help you keep your sight.

How it's diagnosed

Doctors check IOP with tonometry, but one reading isn’t enough. They’ll also measure central corneal thickness (CCT), examine the optic nerve (cup-to-disc ratio), and run visual field testing. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) gives a detailed look at nerve fiber layers. Gonioscopy checks drainage angle anatomy. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) found that thinner corneas (roughly under 555 µm), higher baseline IOP, older age, and larger cup-to-disc ratio raise the risk of turning into glaucoma.

Treatment and monitoring

Treatment depends on your individual risk. Low-risk people often get regular monitoring—maybe every 6–12 months. Higher-risk patients may need drops, laser, or closer follow-up every 3–4 months. The OHTS showed that lowering IOP can cut the chance of developing glaucoma roughly in half over several years, so early action matters when risk is high.

Common eye drops: prostaglandin analogs (once-daily, very effective), beta-blockers (can lower pulse or affect asthma), alpha agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Side effects vary: prostaglandins can darken lashes or change iris color, beta-blockers can cause tiredness or breathing issues, and some drops sting or cause bitter taste. Stick with prescribed dosing and tell your doctor about other health problems or medications.

Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) is a non-drug option that lowers pressure by improving drainage. It’s a quick outpatient procedure and can be used as initial therapy or when drops aren’t enough. Surgical options are rare for ocular hypertension but may appear if pressure stays high despite treatment.

Practical tips: avoid long-term steroid eye drops unless monitored, mention family history of glaucoma, get regular eye exams with visual fields and OCT, and take medications consistently. Moderate aerobic exercise can slightly lower IOP; avoid sustained head-down positions and heavy Valsalva maneuvers. If you have heart or lung issues, mention them before starting certain eye drops.

If you’ve been diagnosed with ocular hypertension, ask your eye doctor about your personal risk level, the pros and cons of starting drops now versus watching closely, and what specific follow-up is best for you. Early, informed decisions give you the best chance to protect your vision.

As a blogger who's passionate about eye health, I've recently come across the significant role brinzolamide plays in treating ocular hypertension. This medication, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, has proven effective in reducing intraocular pressure by decreasing the production of aqueous humor. The ease of administering it as eye drops makes it a convenient option for patients. Moreover, it's often combined with other medications for optimal results. Overall, brinzolamide is an essential treatment for managing ocular hypertension and preventing further complications like glaucoma.

Read more