Diuretic Electrolyte Risk Checker

Check Your Diuretic Safety

This tool identifies dangerous combinations with diuretics based on your medications and demographics. Always consult your doctor before changing any medication.

Diuretics are some of the most commonly prescribed pills for high blood pressure, heart failure, and swelling. But they’re not harmless. Every time you take one, your body loses more than just water. You’re also losing key minerals like sodium, potassium, and chloride - and sometimes too much of them. The problem isn’t just the diuretic itself. It’s what you take with it. A simple antibiotic, a painkiller, or even a new heart medication can turn a safe dose into a dangerous one.

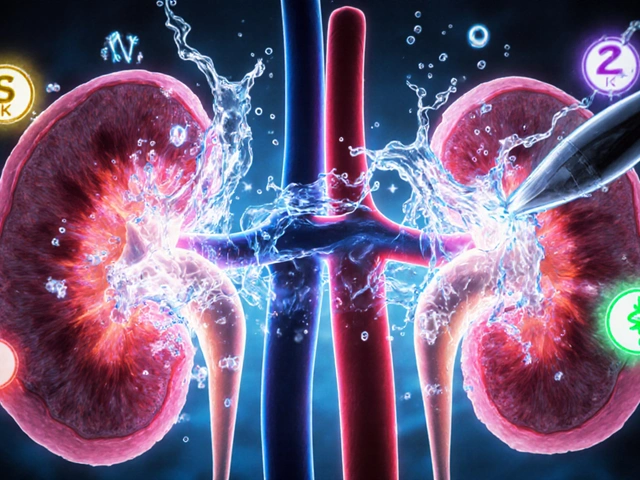

How Diuretics Work - And Why They Mess With Your Electrolytes

Diuretics don’t just make you pee more. They target specific parts of your kidneys to stop sodium from being reabsorbed. When sodium leaves, water follows. That’s how they reduce fluid buildup. But sodium doesn’t travel alone. It drags other electrolytes with it - and that’s where things go wrong.

Loop diuretics like furosemide hit the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. They block the NKCC2 transporter, which normally reabsorbs about 25% of filtered sodium. That’s powerful. One dose of furosemide can make you lose 20-25% of your filtered sodium. But it also knocks out potassium, magnesium, and calcium. That’s why people on loop diuretics often end up with low potassium - hypokalemia.

Thiazides like hydrochlorothiazide work lower down, in the distal convoluted tubule. They’re weaker - only blocking 5-7% of sodium - but they’re longer-lasting. That’s why they’re used daily for high blood pressure. But here’s the catch: they’re notorious for causing hyponatremia, especially in older women. Why? Because they mess up your kidney’s ability to dilute urine. Water stays, sodium gets washed out.

Potassium-sparing diuretics like spironolactone and amiloride do the opposite. They block aldosterone or sodium channels in the collecting duct. This keeps potassium in - great for people who lose too much. But it also means potassium can build up. Hyperkalemia isn’t just a lab number. When potassium hits 6.0 mmol/L or higher, your heart can stop. And it doesn’t always come with warning signs.

The Real Danger: When Diuretics Combine With Other Drugs

Most electrolyte emergencies from diuretics don’t happen because of one pill. They happen because of combinations.

Take NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen. People take them for arthritis or headaches. But they block prostaglandins - chemicals your kidneys need to keep blood flowing during diuretic therapy. Studies show NSAIDs can cut the effect of furosemide by 30-50%. That means swelling doesn’t go down. So doctors add more diuretic. And then the electrolytes crash.

Then there’s the ACE inhibitor trap. These drugs - lisinopril, enalapril - are great for heart failure. They lower blood pressure and protect the kidneys. But when paired with a thiazide, they boost the diuretic effect and cut hypokalemia risk. Sounds good, right? Until you add a potassium-sparing diuretic like spironolactone. Now you’ve got three drugs working together to raise potassium. A 2019 meta-analysis found this combo can spike potassium by 1.2 mmol/L - more than double the risk of monotherapy. One patient I read about had a K+ of 6.8 after starting Bactrim while on spironolactone. He ended up in the ICU.

SGLT2 inhibitors like dapagliflozin were developed for diabetes. But they’re now used in heart failure too. They work by making your kidneys dump glucose - and sodium - into urine. That sounds harmless. But when you combine them with a loop diuretic? The effect multiplies. One study showed bumetanide’s natriuretic effect jumped 36% after adding dapagliflozin. Dapagliflozin’s effect soared 190%. That’s not synergy - it’s a storm. Your kidneys are being hit from two directions. You can lose too much sodium, too fast. And if you’re not monitoring, you won’t know until you’re dizzy, confused, or in shock.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

It’s not just the elderly. It’s the elderly with heart failure, kidney problems, or both. A 2013 study of 20,000 ER patients found that 3% were on multiple diuretics. That group had the highest death rates. Why? Because their kidneys were already struggling. Adding a diuretic that pushes them harder - or mixing drugs that amplify side effects - is like overloading a weak engine.

Women over 70 on thiazides are 3x more likely to get hyponatremia than men. Why? Lower muscle mass. Less total body water. Slower kidney clearance. A single 12.5mg tablet of hydrochlorothiazide can be enough to drop sodium below 130 mmol/L in this group.

People with cirrhosis are another high-risk group. Their bodies hold onto sodium like a sponge. Loop diuretics alone often don’t cut it. Doctors add spironolactone. Then they add a thiazide like metolazone. That’s called sequential nephron blockade. It works - 68% of patients respond. But 22% develop acute kidney injury. 15% get dangerously low sodium. It’s a tightrope walk.

How to Stay Safe - Practical Rules

There’s no magic formula. But there are rules that save lives.

- Check electrolytes within 3-7 days after starting or changing a diuretic. Don’t wait for symptoms. Hyponatremia can sneak up. Hyperkalemia can kill before you feel anything.

- Never combine potassium-sparing diuretics with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or NSAIDs without close monitoring. If you’re on spironolactone and get prescribed an antibiotic like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ask your doctor if it’s safe. It’s not.

- For elderly patients, start low with thiazides. 12.5mg hydrochlorothiazide is often enough. Higher doses increase hyponatremia risk without adding benefit.

- Loop diuretics should be dosed by kidney function. If your eGFR is below 30, you need more furosemide per kg. But don’t just crank it up. Monitor urine output and weight daily.

- Watch for signs of imbalance. Muscle cramps, weakness, confusion, irregular heartbeat, nausea - these aren’t just "side effects." They’re red flags.

One hospital in Baltimore cut hyponatremia cases by 37% and hyperkalemia by 29% in 18 months - not by changing drugs, but by adding automatic electrolyte alerts in their electronic records. When a patient on furosemide and spironolactone got a new prescription for lisinopril, the system flagged it. A pharmacist called the doctor. A crisis was avoided.

New Developments - And Why They Matter

The game is changing. In January 2024, the FDA approved Diurex-Combo - a single pill with furosemide and spironolactone. It’s designed to balance potassium loss and gain. In a trial, it cut heart failure readmissions by 22% and electrolyte emergencies by more than half. That’s huge.

But the real shift is in how we think about diuretics. They’re no longer just "water pills." They’re part of a system. SGLT2 inhibitors are now recommended alongside diuretics for heart failure. They reduce the dose you need. Less diuretic = less risk.

Future tools will use biomarkers to pick the right diuretic. If your urine aldosterone is high, spironolactone will work best. If your chloride excretion is above 0.5%, add a thiazide. These aren’t lab curiosities - they’re becoming standard in top hospitals.

And soon, AI algorithms may predict your risk before you even take a pill. Mayo Clinic’s pilot study showed an AI model could reduce electrolyte emergencies by 40% by analyzing age, kidney function, current meds, and lab history. That’s not sci-fi. It’s coming.

Bottom Line

Diuretics save lives. But they’re not safe by default. The risk isn’t in taking them - it’s in taking them without understanding how they interact with your body and your other drugs. The best diuretic isn’t the strongest one. It’s the one that matches your kidneys, your age, your other conditions, and your other meds. If you’re on a diuretic, ask your doctor: "What electrolytes should I check? When? And what drugs could make this dangerous?" Don’t wait for a crisis to ask.

Comments

Loop diuretics induce natriuresis via NKCC2 inhibition, but concomitant hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are inevitable without aldosterone modulation. The real issue is polypharmacy-induced renal tubular crosstalk.

While the pharmacodynamics are accurately described, the clinical implications are underemphasized. Electrolyte disturbances from diuretics are among the most common causes of preventable hospital readmissions in geriatric cardiology. A 70-year-old woman on hydrochlorothiazide and lisinopril requires electrolyte monitoring within 72 hours-not 7 days. The 3x higher hyponatremia risk in elderly women is not anecdotal; it’s rooted in reduced total body water and diminished glomerular filtration reserve. This isn’t just about drugs-it’s about physiological vulnerability.

Moreover, the FDA’s approval of Diurex-Combo represents a paradigm shift: fixed-dose combinations reduce adherence errors and drug-drug interaction risks. But they’re only as safe as the monitoring protocol. Automated EHR alerts, like the Baltimore hospital’s, should be mandatory, not exceptional. We’ve known for decades that potassium-sparing diuretics + ACEi + trimethoprim = cardiac arrest waiting to happen. Why are we still surprised?

Diuretics are the silent assassins of the medical world. One minute you’re taking a pill for swelling, the next you’re flatlining because some doctor thought ‘it’s just water’ and threw in a NSAID like it was sugar. I’ve seen it-patients in the ER with K+ of 7.1, no symptoms, no warning. Just a quiet death in a hospital bed. And the worst part? It’s 100% avoidable. We’re not talking about rare side effects-we’re talking about predictable, textbook disasters that happen every single week. Why are we still playing Russian roulette with kidney meds?

It’s embarrassing that we still need to explain this in 2024. If you’re prescribing spironolactone with an ACE inhibitor and not checking potassium weekly, you’re not a doctor-you’re a liability. And don’t get me started on the ‘start low, go slow’ crowd. If you’re prescribing thiazides to elderly women without considering body water percentage, you’re practicing outdated medicine. This isn’t complicated. It’s basic physiology. If you can’t handle it, stop prescribing.

As someone who’s worked in renal clinics across three continents, I’ve seen this pattern repeat everywhere-from rural Ohio to Lagos. The science is universal: diuretics don’t discriminate by country, but access to monitoring does. In Nigeria, we rarely have labs to check potassium daily. So we rely on clinical signs: muscle weakness, arrhythmias, fatigue. We teach patients to recognize those. It’s not ideal, but it saves lives when resources are scarce. The real innovation isn’t AI or combo pills-it’s empowering patients to be their own first line of defense.

And yes, SGLT2 inhibitors are game-changers. They’re not just glucose-lowering agents anymore-they’re cardiorenal protectors that reduce diuretic burden. But we still need to train clinicians to see them that way. Too many still think of them as ‘diabetes drugs.’

I appreciate the depth of this post. It’s clear a lot of thought went into explaining how these drugs interact. I’ve had a family member on furosemide and spironolactone, and we didn’t realize how easily things could go wrong. The part about NSAIDs reducing diuretic effectiveness by 30-50% was eye-opening. We were giving ibuprofen for back pain without knowing it could make the whole treatment less effective-or worse. I’m going to share this with my doctor and ask for a simple electrolyte check schedule. Thanks for making this so understandable.

You’re all missing the point. The real problem isn’t the drugs-it’s the patients. People take OTC meds like candy. They don’t read labels. They don’t tell their doctors about every supplement or painkiller they’re popping. Then they wonder why they’re in the hospital. It’s not the doctor’s fault. It’s the patient’s lack of responsibility. If you can’t manage your own meds, maybe you shouldn’t be on them. Stop blaming the system. Fix the people.

Of course Americans are shocked by this. You medicate everything. You think a pill fixes everything. In Europe, we don’t hand out diuretics like candy. We test, we monitor, we wait. You want a quick fix? Fine. But don’t act surprised when your kidneys give out because you took Advil with your water pill. This is what happens when you treat medicine like a fast-food menu.

Look, I’ve been on a diuretic for years-just for mild swelling, nothing serious. I never thought twice about it until my cousin ended up in the ICU after mixing her meds. That’s when I started reading. Turns out, I was taking melatonin and turmeric supplements-both of which can mess with potassium. I stopped them. Got my levels checked. All good. Point is, it’s not just the big drugs. It’s everything. Even that ‘natural’ thing you think is harmless? Could be a silent killer. So yeah, ask your doc. Even if it feels dumb. Better safe than sorry.