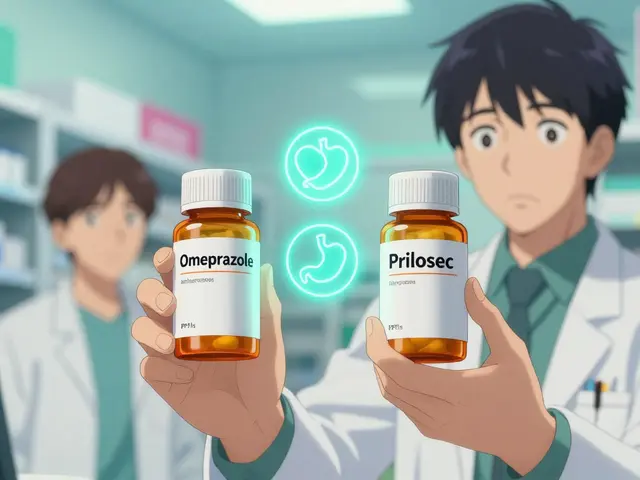

When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might see a name like omeprazole instead of Prilosec. That’s a generic drug. But behind that simple name is a whole system designed to organize thousands of medications so doctors, pharmacists, and insurers know exactly what they’re dealing with. Generic drug classifications aren’t just labels-they’re the backbone of safe, efficient, and legal prescribing. Without them, prescribing the right drug, avoiding dangerous interactions, or even getting insurance coverage would be chaos.

Therapeutic Classification: What the Drug Treats

The most common way to classify drugs is by what condition they treat. This is called therapeutic classification. It’s the system your doctor uses every day. If you have high blood pressure, your doctor doesn’t think, ‘Which chemical structure should I prescribe?’ They think, ‘Which cardiovascular agent works best here?’

The FDA and USP use a detailed hierarchy for this. Major categories include:

- Analgesics (pain relievers)

- Antihypertensives (blood pressure drugs)

- Antibiotics

- Antidepressants

- Antidiabetics

- Antineoplastics (cancer drugs)

- Endocrine agents (hormone treatments)

Each of these has subcategories. Under Analgesics, you’ll find Non-opioid (like ibuprofen) and Opioid (like morphine). Under Antihypertensives, you’ll see ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers. This system helps doctors choose the right drug for the right condition-and avoid duplicates. If you’re already on a beta-blocker for blood pressure, your doctor won’t accidentally add another one.

But it’s not perfect. Some drugs treat more than one thing. Aspirin reduces pain, prevents blood clots, and lowers fever. Is it an analgesic, an anticoagulant, or an anti-inflammatory? In therapeutic classification, it usually gets listed under its primary use, which can confuse patients and providers. The FDA’s new Therapeutic Categories Model 2.0, rolling out in 2025, will allow drugs to have a primary and secondary indication, fixing this problem.

Pharmacological Classification: How the Drug Works

While therapeutic classification asks, ‘What does it do?’ pharmacological classification asks, ‘How does it do it?’

This system groups drugs by their mechanism of action-how they interact with the body at a molecular level. For example, all beta-blockers end in ‘-lol’ (like metoprolol, propranolol). That’s not a coincidence. It’s a naming rule designed to tell you instantly what kind of drug it is.

Other examples:

- ‘-prazole’ = proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, pantoprazole)

- ‘-dipine’ = calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, nifedipine)

- ‘-sartan’ = angiotensin II receptor blockers (losartan, valsartan)

There are over 87 of these standardized stems recognized by the USP. They’re not just for naming-they reduce medication errors. A 2022 study found that using stem-based naming cut prescribing mistakes by 18% in hospitals.

Pharmacological classification is more precise than therapeutic classification. It explains why two drugs from different therapeutic groups might interact. For example, fluoxetine (an antidepressant) and warfarin (a blood thinner) both affect liver enzymes. Even though one treats depression and the other prevents clots, their shared pharmacological pathway means they can’t be mixed safely.

The downside? You need a science background to understand it. A nurse or patient might not know what a ‘kinase inhibitor’ is, even if it’s the exact drug they’re taking. That’s why most frontline providers rely on therapeutic classification for daily decisions.

DEA Schedules: Legal Status and Abuse Risk

Not all drugs are created equal under the law. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classifies controlled substances into five schedules based on two things: how likely they are to be abused, and whether they have accepted medical uses.

Here’s how it breaks down:

- Schedule I: No medical use, high abuse potential. Examples: heroin, LSD, marijuana (federally). This category is controversial-38 states allow medical marijuana, but the DEA still lists it as Schedule I.

- Schedule II: High abuse potential, but medical use. Examples: oxycodone, fentanyl, Adderall, cocaine.

- Schedule III: Moderate abuse potential, accepted medical use. Examples: ketamine, buprenorphine, anabolic steroids.

- Schedule IV: Low abuse potential. Examples: alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), zolpidem (Ambien).

- Schedule V: Lowest abuse potential. Examples: cough syrups with small amounts of codeine (under 200mg per 100ml).

This system affects prescriptions. Schedule II drugs can’t be refilled. They require a written or electronic prescription. Schedule III-V drugs can sometimes be called in or refilled up to five times. Pharmacists check these schedules daily. If a patient asks for a refill on a Schedule II drug two weeks early, the pharmacist knows to flag it.

But there’s inconsistency. Oxycodone is Schedule II and causes more overdose deaths than heroin. Marijuana is Schedule I despite FDA-approved cannabinoid drugs like dronabinol, which is Schedule II. Critics say the system is outdated and doesn’t reflect science-it reflects politics.

Insurance Tiers: What You Pay Out of Pocket

Insurance companies don’t care about mechanism or legal status. They care about cost. That’s why they created tiered formularies.

Most plans use a five-tier system:

- Tier 1: Preferred generics. Lowest cost. Usually under $10 per month. About 75% of generics fall here.

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics. Slightly higher cost. Might be a different brand or formulation.

- Tier 3: Preferred brand-name drugs. More expensive. Often requires prior authorization.

- Tier 4: Non-preferred brands. High cost. Usually not covered unless you prove no generic works.

- Tier 5: Specialty drugs. Very high cost. Often injectables or oral cancer drugs. Can cost hundreds or thousands per month.

Here’s the catch: two identical generic drugs can be on different tiers. Why? Because the insurance company made a deal with one manufacturer but not another. A 2022 KFF analysis found patients paid 25-35% more for a Tier 2 generic than a Tier 1 generic-even though the active ingredient was exactly the same.

Pharmacists spend hours fighting these decisions. About 43% of prior authorization requests come from tier disputes, according to Reddit’s r/pharmacy community. Patients get frustrated: ‘I’m paying more for the same pill?’ But insurers say it’s about steering patients toward cheaper options. It’s a system built on economics, not medicine.

ATC Classification: The Global Standard

While the U.S. uses multiple systems, the world mostly follows the WHO’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system. It’s the only classification that’s truly global.

ATC uses five levels:

- Level 1: Anatomical main group (e.g., A = Alimentary tract and metabolism, C = Cardiovascular system)

- Level 2: Therapeutic subgroup (e.g., C03 = Diuretics)

- Level 3: Pharmacological subgroup (e.g., C03A = High-ceiling diuretics)

- Level 4: Chemical subgroup (e.g., C03CA = Sulfonamides)

- Level 5: Chemical substance (e.g., C03CA01 = Furosemide)

So furosemide’s full ATC code is C03CA01. That one code tells you where it acts (cardiovascular), what it does (diuretic), how it works (sulfonamide), and what it is (furosemide). It’s used in 143 countries and updated every quarter. In 2022 alone, 217 new drugs got ATC codes.

It’s not perfect. It doesn’t capture multi-use drugs well. But it’s the most consistent system for research, global drug tracking, and public health reporting. If you’re reading a study on medication use in Germany or Brazil, they’re almost certainly using ATC codes.

Why This Matters to You

You might think classification systems are just for doctors and pharmacists. But they affect you directly.

- If your insurance denies your prescription, it’s because of tier rules.

- If you get a dangerous drug interaction, it’s because someone missed a pharmacological overlap.

- If you’re prescribed a Schedule II drug and can’t refill it, it’s because of DEA rules.

And confusion is real. A 2023 survey found 68% of physicians say mixing up therapeutic and pharmacological classifications leads to prescribing errors. Nurses spend extra time verifying drugs because the system isn’t unified. Patients waste hours on hold trying to get a generic approved when it’s the same as the brand-name drug.

The good news? Systems are improving. The FDA’s new model will let drugs have multiple uses. AI tools like IBM Watson’s Drug Insight are learning to predict the best classification for new drugs. And more providers are training on these systems.

But until everything talks to everything else-therapeutic, pharmacological, DEA, insurance, and ATC-there will be gaps. Knowing how these systems work helps you ask better questions. Ask your pharmacist: ‘Is this the same as the brand name?’ Ask your doctor: ‘Is this on Tier 1?’ Ask your insurer: ‘Why is this generic in Tier 2?’

Understanding drug classifications isn’t about memorizing codes. It’s about taking control of your care.

What’s the difference between generic and brand-name drug classifications?

There’s no difference in classification. Generic and brand-name drugs with the same active ingredient are classified the same way-therapeutically, pharmacologically, legally, and by insurance tier. The only difference is the manufacturer and price. A generic omeprazole has the same ATC code (A02BC01), same DEA schedule (none, since it’s not controlled), and same therapeutic category (proton pump inhibitor) as Prilosec. Insurance may place them on different tiers based on contracts, but the drug itself is identical.

Why is marijuana still a Schedule I drug if it’s legal in many states?

Marijuana is classified as Schedule I by the DEA because, under federal law, it has no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. But 38 states allow medical use, and the FDA has approved cannabinoid-based drugs like dronabinol (Schedule II). This contradiction exists because federal and state laws don’t align. The MORE Act, passed by the House in 2023, would reclassify marijuana as Schedule III, but it’s stalled in the Senate. Until federal law changes, marijuana remains Schedule I nationally.

Can a drug be in two therapeutic categories?

Traditionally, no-most systems forced drugs into one category. Aspirin, for example, was usually listed as an analgesic, even though it also prevents blood clots. But the FDA’s new Therapeutic Categories Model 2.0, launching in 2025, will allow drugs to have a primary and secondary indication. This means a drug like duloxetine can be listed as both an antidepressant and a neuropathic pain treatment. It’s a major step toward recognizing real-world prescribing.

How do drug stems help prevent errors?

Drug stems are the endings in generic names that tell you the drug’s class. ‘-lol’ means beta-blocker, ‘-prazole’ means proton pump inhibitor, ‘-dipine’ means calcium channel blocker. When a doctor writes ‘metoprolol,’ any pharmacist knows it’s a beta-blocker-even if they’ve never heard the name before. This reduces confusion with similar-sounding drugs. Studies show this system cuts prescribing errors by 18%. It’s one of the simplest, most effective safety tools in medicine.

Why do two identical generic drugs cost different amounts?

Because insurance companies negotiate deals with manufacturers. One company might pay a lower price to get their generic placed on Tier 1 (preferred). Another company’s identical drug ends up on Tier 2 (non-preferred) because they didn’t make the deal. The active ingredient, dosage, and effectiveness are the same. But the price isn’t. This isn’t about quality-it’s about contracts. Always ask your pharmacist: ‘Is there a cheaper version?’ You might be paying more for no reason.

Comments

This is such a clear breakdown! I never realized how much goes into just one pill. The stem thing? Genius. 🙌

I work in a pharmacy and this is exactly why I lose sleep at night. Patients come in asking why their $3 generic is now $28 even though it’s the same damn pill. Insurance contracts are a nightmare.

The fact that aspirin gets shoved into one category while being three drugs in one really shows how broken the system is. We need to stop forcing medicine into boxes and start seeing it as the messy, beautiful science it is. 🌱

This is why America’s healthcare is a joke. Schedule I for marijuana while fentanyl is Schedule II? Who wrote this? A politician with a degree in marketing? The DEA is a relic. Fix this or shut it down.

In India, we use ATC codes every day. It’s the only system that doesn’t make you want to scream. I wish more US docs would just adopt it. Less confusion, more clarity. Simple.

The pharmacological classification system, particularly the standardized nomenclature stems, represents a critical epistemological framework for pharmacovigilance and clinical decision-making. The empirical validity of stem-based error reduction, as cited in the 2022 study, is statistically significant (p < 0.01) and warrants institutional adoption across all prescriptive tiers.

I’ve seen this play out in my family. My mom’s blood pressure med got switched to a Tier 2 generic because the insurer cut a deal with a different maker. She got sick for weeks. Turns out the filler was different. Same active ingredient, different body. The system doesn’t care.

You people are overcomplicating this. If you can’t read a label and understand that generics are cheaper versions of the same drug, you shouldn’t be allowed to take pills. Stop blaming the system. Blame your own laziness.

The FDA and WHO systems are the only ones that matter. Anything else is just noise. America needs to stop reinventing the wheel and start following global standards. End of story