Most people assume their insurance covers generics at a low cost-until they see the bill. A $50 copay for a generic blood pressure pill? That’s not a mistake. It’s the result of a broken system where insurers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and manufacturers play a high-stakes game of pricing that rarely benefits the patient. But behind the scenes, smart insurers are fixing this by using bulk buying and tendering to cut generic drug costs by up to 90%. Here’s how they do it-and why you might not be seeing those savings yet.

What Bulk Buying and Tendering Really Mean

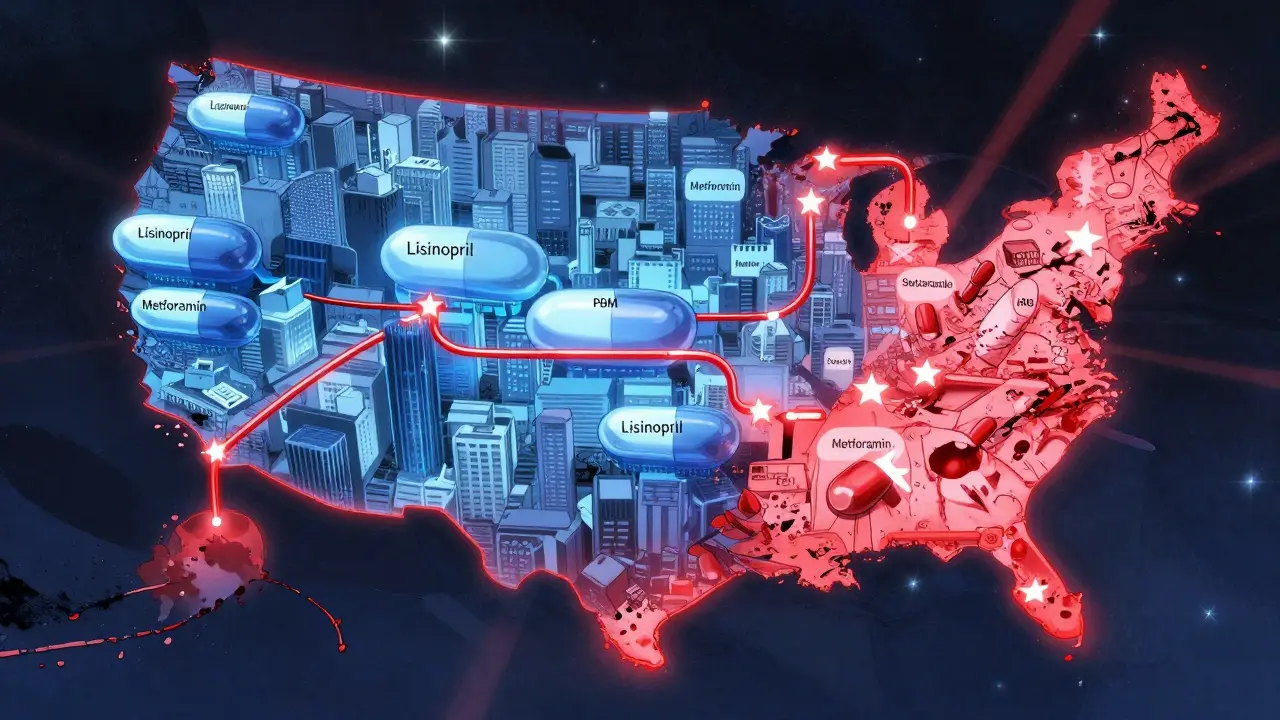

Bulk buying isn’t just buying in large quantities. It’s about using market power to force prices down. When an insurer or PBM commits to buying millions of pills of a specific generic drug-say, lisinopril or metformin-they don’t just ask for a discount. They open the door to a competitive bidding process called tendering. Multiple manufacturers submit bids. The lowest price wins, and the insurer locks in that rate for a year or two.

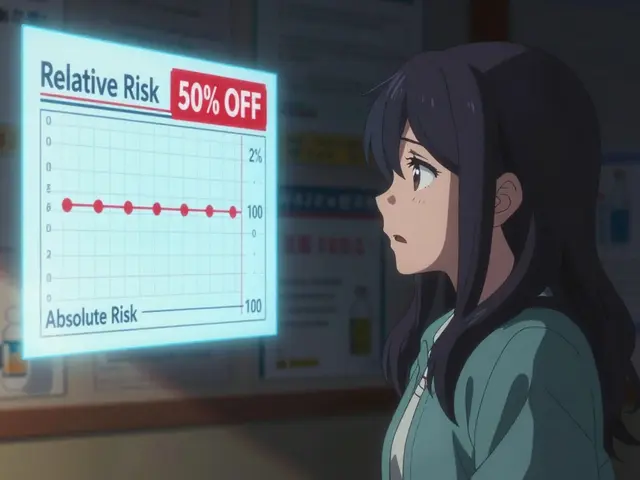

This isn’t theoretical. In 2022, a JAMA Network Open study found that when insurers switched from high-cost generics to lower-cost alternatives with the same active ingredient, they saved nearly 90%. That’s not a small win. It’s life-changing for people paying out-of-pocket. But here’s the catch: many insurers don’t do this well. Some actually pay more for generics because their PBM’s formulary is designed to maximize profit, not savings.

The Hidden Game: Spread Pricing and Opaque Formularies

Most people think their insurance company negotiates directly with pharmacies. It’s not that simple. Enter the pharmacy benefit manager-companies like OptumRx, Caremark, and Express Scripts. These are middlemen hired by insurers to manage drug benefits. But many PBMs don’t just negotiate prices. They create a gap between what they pay the pharmacy and what they charge the insurer. That gap? It’s called spread pricing.

Here’s how it works: A PBM tells the insurer they’ll pay $10 for a generic pill. But they only pay the pharmacy $4. The $6 difference? That’s profit. And here’s the kicker: they often choose higher-priced generics because they get bigger rebates from manufacturers. So even though a cheaper version exists, your plan might still cover the expensive one. You’re stuck paying a $30 copay because the system rewards high prices, not low ones.

A 2022 study showed that 78% of Medicare Part D plans put generics on higher tiers with bigger copays-even though those drugs cost less than $1 to make. That’s not a pricing error. It’s a design flaw.

How Insurers Actually Save: The Tendering Process

Smart insurers skip the PBM middleman and go straight to manufacturers. They identify drugs where multiple generic makers compete-like atorvastatin or levothyroxine-and run a formal tender. They ask: “Who can supply 5 million tablets of this drug for the lowest price per unit?”

Manufacturers respond with bids. The insurer picks the lowest. They sign a contract for 1-3 years. In return, the manufacturer gets guaranteed volume. It’s a win-win: the insurer pays less, the manufacturer sells more. And because generics have no R&D costs, manufacturers can afford to bid aggressively.

The results are dramatic. According to the FDA, the first generic version of a drug saves an average of $5.2 billion in its first year. One generic version of the cancer drug pemetrexed saved over $1 billion in 12 months. That’s not a fluke. It’s the power of competition.

Transparency Works: Cost Plus Drug Company and Direct-to-Consumer Models

Some insurers and employers are bypassing PBMs entirely. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company, for example, charges manufacturers’ cost plus 15% plus a $3 pharmacy fee. No spreads. No rebates. No hidden fees. A 2023 NIH study found these models save patients 76% on expensive generics and 75% on common ones. For a $200 prescription, that’s $150 saved.

Blueberry Pharmacy, another transparent model, reports average savings of $200 per year per member. One user wrote: “My blood pressure med costs exactly $15/month. No surprises. No insurance hoops.” That’s the kind of clarity insurers want-but rarely deliver.

Even GoodRx and other cash-price apps are proving that consumers know the truth: sometimes paying cash is cheaper than using insurance. In 2020, 97% of cash payments for prescriptions were for generics. People aren’t being irrational. They’re just avoiding a broken system.

Why Some Generics Still Cost Too Much

Not all generics are created equal. Some drugs have only one or two manufacturers. When competition drops, so does price pressure. The FDA found that 80% of certain generic drugs are made by just three companies. That’s a recipe for shortages-and price spikes.

In 2020, albuterol inhalers disappeared from shelves because manufacturers couldn’t profit at the prices set by insurers. The same thing happened with doxycycline and metformin. When tendering drives prices below production cost, companies walk away. And when only one company is left, they raise prices.

That’s why smart insurers don’t just chase the lowest bid. They monitor supply chains. They keep multiple manufacturers on contract. They avoid drugs with only one supplier. They know that long-term savings depend on stable competition, not just one-time discounts.

What Insurers Are Doing Right (And What They Should Change)

Leading insurers now run quarterly reviews of their generic drug spending. They look for outliers-drugs where the price is way above the market average. They check how many manufacturers make the drug. If there are five, they tender. If there’s one, they look for alternatives.

Some are also adding transparency clauses to PBM contracts. California’s Senate Bill 17 requires PBMs to disclose any price difference over 5% between what they pay pharmacies and what they charge insurers. That’s a start. But most states don’t have it.

Another move? Shifting from fee-for-service to value-based contracts. While this is common for expensive specialty drugs, few insurers apply it to generics. That’s a missed opportunity. Why not pay a lower price per pill if the drug keeps patients out of the hospital?

What You Can Do

If you’re on insurance and paying too much for generics, here’s what to do:

- Check your copay. Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices.

- If the cash price is lower, ask your pharmacist to process it as cash. Your insurer doesn’t need to know.

- Ask your employer or insurer: “Do you use transparent tendering for generics? Can I see your formulary pricing data?”

- If you’re self-employed or your employer offers a health savings account (HSA), consider switching to a direct-to-consumer pharmacy like Cost Plus Drug Company.

Don’t assume your insurance is working for you. The system is designed to hide savings. But you don’t have to play by its rules.

The Bigger Picture: $445 Billion in Savings-And Why It’s Not Reaching You

In 2023, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $445 billion. That’s more than the GDP of Ireland. $194 billion of that went to adults aged 40-64. But if you’re paying $50 for a $3 pill, you’re not seeing it.

The savings are real. They’re just being captured by PBMs, not patients. The solution isn’t more regulation-it’s more transparency. More competition. More accountability.

Insurers that use bulk buying and tendering correctly aren’t just cutting costs. They’re restoring trust. They’re proving that healthcare doesn’t have to be expensive to be effective. The tools exist. The data is clear. The question is: who’s going to use them?

Comments

man i just paid $42 for metformin last week and i swear i saw it for $8 on goodrx. this whole system is rigged. why am i paying more just because i have insurance??

PBMs are the real villains here. 🤬 They’re not intermediaries-they’re parasites. Insurers think they’re saving money but they’re just letting middlemen skim off the top while patients bleed out. Time to burn the whole system down.

The tendering model is fundamentally sound-it’s basic procurement economics. When you aggregate demand and enforce competitive bidding, you drive down marginal cost. The failure isn’t the mechanism, it’s the perverse incentives embedded in PBM contracts. Spread pricing violates the fiduciary duty insurers owe to their enrollees. Transparency mandates like CA SB-17 are a start, but we need federal legislation to mandate pass-through pricing and ban rebate-based formulary placement.

Just want to say-this is the most clear-headed breakdown of the generic drug mess I’ve seen. People think it’s about greed, but it’s really about misaligned incentives. PBMs profit when prices are high, not low. And patients get stuck in the middle. You’re right: the tools exist. It’s just a matter of willpower. Keep pushing this narrative.

Interesting how this mirrors what happens in public procurement globally. In South Africa, we’ve seen similar dynamics with HIV antiretrovirals-when bulk tendering was introduced, prices dropped 80% in two years. The key was excluding middlemen and enforcing local manufacturing partnerships. The US could replicate this if it stopped treating healthcare like a stock market. Competition isn’t a buzzword-it’s a lever.

Let’s be precise: the FDA’s 2023 data shows that 67% of generic drugs have 3+ manufacturers, but only 22% of formularies actively tender for them. The rest rely on PBM-managed contracts with opaque rebate structures. The real bottleneck isn’t supply-it’s contracting inertia. Insurers need to adopt reverse auction platforms like those used by the VA. They’ve cut costs 60-75% on top generics without compromising access.

bro i just checked my script for lisinopril-$52 with insurance, $11 cash. i’ve been using goodrx for 6 months now. no one tells you this stuff. why does the system make it so hard to save money? it’s like they want us to suffer.

Of course the system’s broken. You think corporations care about your health? They care about margins. You’re not a patient-you’re a revenue stream. If you’re not paying cash, you’re subsidizing their greed. Stop trusting insurance. It’s not your friend.

PBMs are the reason we can’t have nice things. They’re like the mafia with pharmacy licenses. And don’t even get me started on how they’re all owned by Big Pharma anyway. It’s a closed loop of corruption. We need to nationalize drug pricing. Or at least ban PBMs. Fuck ‘em.

So let me get this straight: the system is designed so that the cheapest option is the one you’re punished for using? Genius. I didn’t know we were running a capitalist simulation game where the goal is to maximize patient suffering. Congrats, America. You’ve won.

Wait… so you’re telling me the whole thing is a scam? That this isn’t just bad luck or bad insurance, but a coordinated effort by corporations to bleed us dry? And they’re using our own data to do it? That’s not capitalism-that’s psychological warfare. I knew it. I always knew it. They’re not selling medicine. They’re selling control.