Absolute vs Relative Risk Calculator

Understand the Numbers

This calculator helps you see the difference between absolute risk and relative risk. Enter baseline risk (the risk without treatment) and the change in risk. You'll see the absolute change, relative change, and what it means in real-world terms.

Input Your Risk Data

Results

What This Means

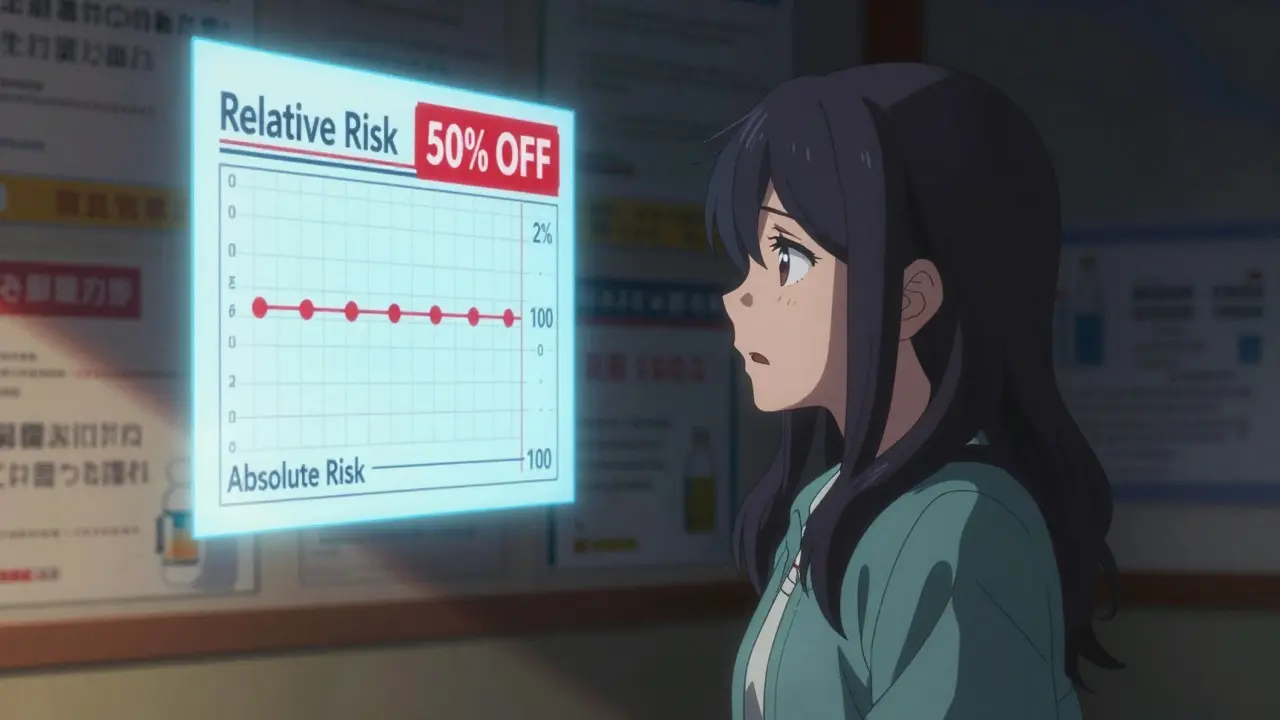

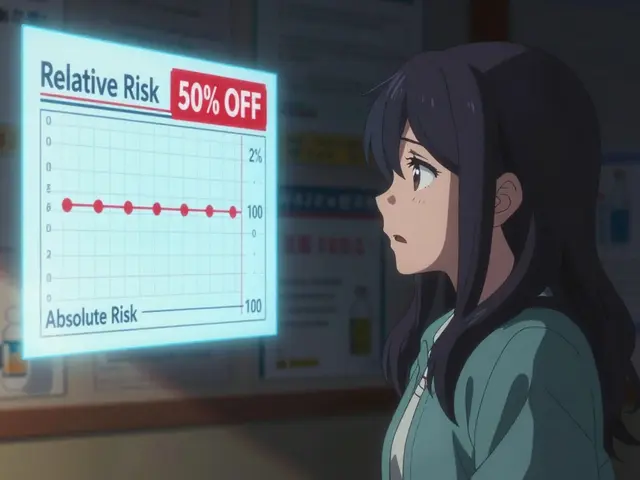

Imagine you’re told a new medication cuts your risk of a heart attack in half. That sounds amazing - until you find out your original risk was only 2%. Halving that means your new risk is 1%. That’s not a miracle drug. It’s a small benefit hidden behind a big number. This is the trap most people fall into when they hear about drug side effects or benefits. The difference between absolute risk and relative risk isn’t just math - it’s the difference between making an informed choice and being misled.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk tells you the actual chance of something happening to you. It’s simple: out of 100 people like you, how many will experience the side effect or benefit? If a drug causes liver damage in 1 out of every 1,000 people, that’s an absolute risk of 0.1%. If it prevents a stroke in 5 out of 100, that’s a 5% absolute benefit. No tricks. No percentages hiding behind other numbers.This is the number that matters most when you’re deciding whether to take a pill. It answers the question: What’s the real impact on my body? A 0.1% chance of liver damage means you’d need to treat 1,000 people before one person has a problem. That’s not common. But if the drug reduces your stroke risk from 10% to 5%, that’s a 5% absolute benefit - meaning 1 in 20 people will avoid a stroke. That’s meaningful.

Doctors and regulators use absolute risk to calculate the Number Needed to Treat (NNT). If a drug has a 5% absolute benefit, the NNT is 20. That means 20 people need to take it for one person to benefit. If the NNT is 100, you’re treating 100 people for one good outcome. That’s a very different picture than hearing it "reduces risk by 50%."

What Relative Risk Tells You (and Doesn’t)

Relative risk compares two groups: people who took the drug versus those who didn’t. It’s a ratio. If the risk of a side effect is 2% in the control group and 4% in the drug group, the relative risk is 2.0 - meaning you’re twice as likely to have the side effect. That sounds scary. But here’s the catch: 2% to 4% is still only a 2 percentage point increase. That’s an absolute risk increase of 2%. Two out of 100 people. Not everyone.Pharmaceutical ads love relative risk because it makes small changes look huge. A drug that reduces heart attack risk from 2% to 1% sounds like a 50% reduction. That’s a 50% relative risk reduction. But the absolute benefit? Just 1 percentage point. One in 100 people benefits. The other 99 get no protection - but still face the same side effects.

Here’s a real example from a statin study: The relative risk reduction for heart attack was 30%. Sounds impressive. But the absolute risk reduction? Just 1.2%. That means for every 100 people taking statins, only 1 or 2 avoid a heart attack. The rest? They’re exposed to muscle pain, diabetes risk, and liver enzyme changes - all for a tiny chance of benefit. If you don’t know the absolute numbers, you think it’s a miracle. It’s not.

Why the Difference Matters So Much

The gap between absolute and relative risk isn’t a technicality - it’s a communication failure. And it’s costing people money, health, and peace of mind.Take the case of a woman in Brisbane who refused a blood pressure drug because the ad said it "reduced stroke risk by 40%." She thought it meant she’d have a 60% lower chance of stroke. But her baseline risk was only 0.5%. The drug brought it down to 0.3%. That’s a 40% relative reduction - but only a 0.2 percentage point absolute drop. She’d need to take it for 500 years to prevent one stroke in her lifetime. She didn’t need the drug. She needed the truth.

Another example: A new antidepressant increases the risk of sexual dysfunction by 2.4 times compared to placebo. That sounds alarming. But if 8% of placebo users had the side effect, and 20% of drug users did, the absolute increase is just 12 percentage points. That’s 12 out of 100 people. Still common - but not a rare, freak accident. Context changes everything.

Without absolute numbers, you can’t judge if the trade-off is worth it. Is a 2% increase in diabetes risk worth a 1% reduction in heart attacks? You can’t answer that if you only know the relative risk.

How the Industry Uses This to Sell Drugs

The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t hide this trick by accident. It’s deliberate. A 2021 study found that 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. used relative risk reductions - and didn’t mention absolute risk at all. Why? Because 50% sounds better than 1%. 90% sounds like a cure. But 0.099%? That’s a whisper.One drug advertised a 90% reduction in cancer risk after a nuclear accident. The absolute risk? Went from 0.75% to 1.25%. That’s a 0.5 percentage point increase - not a 90% danger. But the headline? "Cancer Risk Skyrockets 90%." That’s fear-driven marketing. And it works.

Marketing teams know that people don’t understand statistics. They also know that fear and hope drive behavior more than facts. So they give you the flashy number - the relative risk - and let you fill in the blanks. Most people assume "50% reduction" means half of people are saved. It doesn’t. It means your personal risk was cut in half - from something small to something even smaller.

How to Read the Numbers Like a Pro

You don’t need a degree in biostatistics to cut through the noise. Here’s how to decode any drug claim:- Find the baseline risk. What’s the chance of the problem happening without the drug? Look for phrases like "in people like you" or "among those with high blood pressure." If it’s not stated, ask.

- Find the absolute benefit or harm. Ask: "How many fewer people had the outcome?" or "How many more had the side effect?" If they only give you percentages like "50% reduction," ask for the actual numbers.

- Calculate the NNT or NNH. If the absolute benefit is 5%, the NNT is 20. If the absolute harm is 3%, the Number Needed to Harm (NNH) is 33. That tells you how many people you need to treat to see one benefit - or one harm.

- Compare the NNT to the NNH. If the NNT is 10 and the NNH is 50, the benefit outweighs the risk. If the NNT is 100 and the NNH is 20, you’re doing more harm than good.

For example: A drug reduces migraine frequency by 50%. Sounds great. But if you have 4 migraines a month, and the drug brings it down to 2, that’s a 50% relative reduction. But the absolute reduction? Just 2 migraines a month. Is that worth the cost, the side effects, and the daily pill? Maybe. But you can’t know unless you see the real numbers.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

Don’t let your doctor skip this part. Ask these questions:- "What’s my risk of this problem without the drug?"

- "How much does the drug actually lower that risk?"

- "What’s the chance I’ll have a side effect?"

- "How many people like me need to take this for one person to benefit?"

- "How many need to take it before one person has a bad reaction?"

If they say, "It cuts your risk in half," ask: "Half of what?" Then write down the numbers. Don’t trust memory. Write it down.

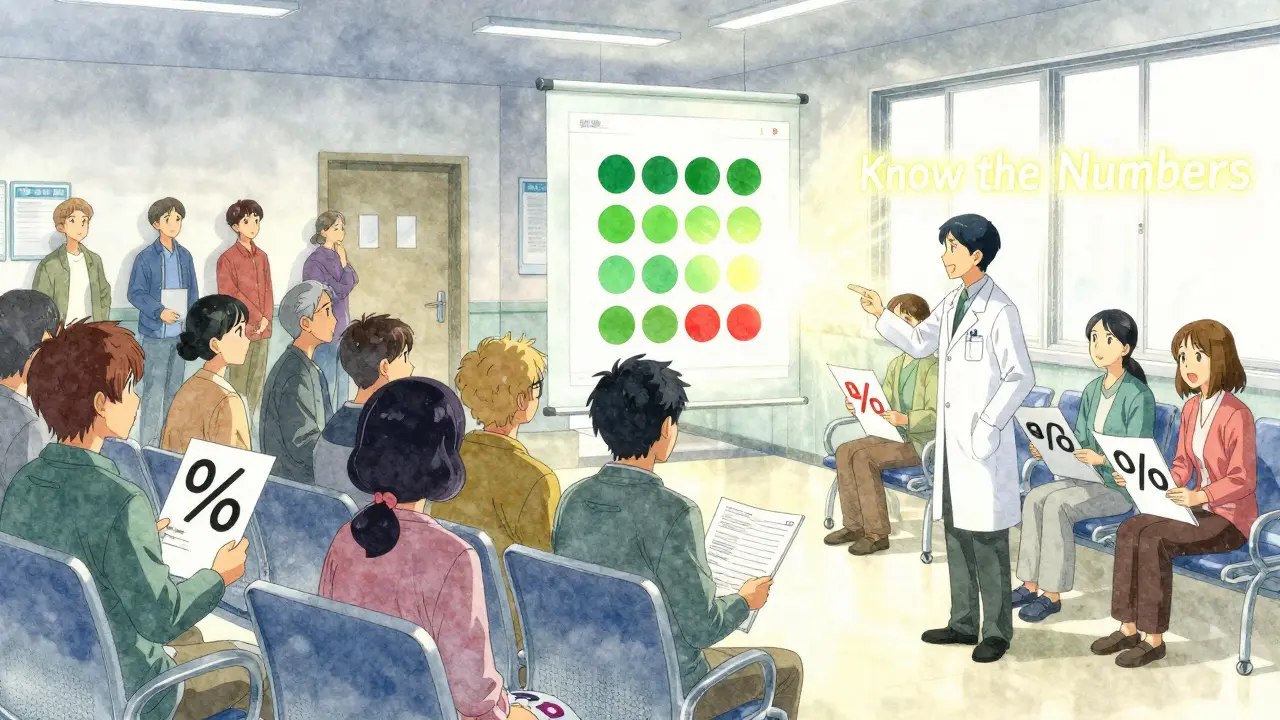

Good doctors will show you charts with 100 little people - 100 dots representing you and others. Some are colored red for side effects, green for benefit. You can see it visually. That’s the gold standard. If they don’t use visuals, ask for them.

The Bottom Line: Numbers Don’t Lie - But People Do

Absolute risk tells you what’s real. Relative risk tells you how it’s sold. You need both - but if you only get one, make it absolute. A 90% relative risk reduction sounds like a miracle. But if your baseline risk was 0.001%, then the absolute reduction is 0.0009%. You’re talking about one person in a million. That’s not a miracle. It’s a statistical ghost.On the other hand, a 10% absolute benefit? That’s 1 in 10 people helped. That’s real. That’s worth talking about.

Next time you see a drug ad, a study, or your doctor mention a "reduction," pause. Ask for the numbers. Write them down. Compare them. Your health isn’t a marketing campaign. It’s your life.

What Happens When You Get It Right

There’s a reason the Cochrane Collaboration and the FDA now push for absolute risk reporting. When patients understand the real numbers, they make better decisions. One study found that when patients saw both absolute and relative risks with visual aids, 62% understood the benefit. When they only saw relative risk? Only 8% got it right.Patients who understood absolute risk were more likely to stick with treatments that truly helped them - and more likely to stop ones that didn’t. That’s not just smarter. It’s safer.

By 2025, most clinical trials will be required to report both absolute and relative risks. That’s progress. But until then, you have to be the one who asks. You have to be the one who reads between the numbers.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk tells you the actual chance of something happening - like a 2% chance of a heart attack. Relative risk compares two groups - like saying a drug cuts your risk in half. The same 2% risk cut in half becomes 1%, which is a 50% relative reduction. Absolute risk shows you the real impact. Relative risk makes the change look bigger.

Why do drug ads use relative risk instead of absolute risk?

Because relative risk numbers are bigger and sound more impressive. Saying a drug reduces risk by 50% sounds better than saying it reduces risk from 2% to 1%. Pharmaceutical companies know people don’t understand statistics, so they use the number that makes the drug look most effective - even if it’s misleading.

How do I know if a drug is actually worth taking?

Look for the absolute benefit and the absolute risk of side effects. Then calculate the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) - how many people need to take it for one to benefit - and the Number Needed to Harm (NNH) - how many need to take it before one has a side effect. If the NNT is much lower than the NNH, it’s likely worth it. If they’re close or the NNH is lower, think twice.

Can I trust my doctor if they only give me relative risk numbers?

Ask for the absolute numbers. A good doctor will give them to you. If they brush you off or say "it’s too complicated," that’s a red flag. You have the right to understand your care. If they can’t explain it simply, get a second opinion.

Are there tools to help me understand these numbers?

Yes. Many health websites, including Cochrane and the FDA, offer visual tools like risk ladders or pictograms that show 100 people - coloring in how many benefit or have side effects. These are far easier to understand than percentages. Ask your doctor if they have one. Or search for "risk visualization tool" online.

Comments

Let me just say this: if you’re still swallowing pharmaceutical marketing fluff without demanding absolute risk numbers, you’re not just uninformed-you’re complicit in your own medical exploitation. The industry doesn’t want you to understand NNT or NNH because transparency kills profit margins. They weaponize relative risk like a magician’s sleight of hand-‘50% reduction!’-while hiding the fact that your baseline risk was 0.8%. That’s not medicine. That’s predatory capitalism dressed in lab coats.

And don’t get me started on doctors who say ‘it’s too complicated.’ If you can’t explain it to a high schooler, you shouldn’t be prescribing it. The Cochrane Collaboration has been screaming this for decades. We’re not talking about quantum physics here. We’re talking about 100 little dots on a page. One color for benefit. Another for harm. You don’t need a PhD to interpret that. You just need the will to demand the truth.

I’ve seen patients refuse statins because they heard ‘increased diabetes risk’-without knowing the absolute increase was 0.5%. Meanwhile, their actual stroke risk dropped from 4% to 3%. That’s a 25% relative reduction, but the absolute benefit? One in 100. The harm? One in 200. That’s a net win. But because they didn’t get the numbers, they walked away. And now they’re on a treadmill, terrified of pills, while their arteries harden. This isn’t just ignorance. It’s a public health crisis.

And yes, I’m angry. Because people die because of this. Not because drugs are bad. But because the system is designed to confuse. The FDA’s 2025 mandate is a start. But until patients stop being passive recipients and start demanding transparency, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Next time your doctor says ‘it cuts your risk in half,’ say: ‘Half of what? Show me the baseline.’ And if they hesitate? Find a new doctor. Your life isn’t a marketing demo.

PS: If you think I’m being dramatic, go read the 2021 JAMA study on DTC ads. 78% used relative risk only. No absolute numbers. Not even a footnote. That’s not an accident. That’s a strategy.

People don’t understand statistics because they don’t want to. They want a magic pill that fixes everything without effort. Absolute risk? NNT? Too much work. Just tell me if it’s good or bad. That’s why pharma wins. Because laziness is the most profitable condition in modern healthcare.

Stop using relative risk. It’s lying. Absolute numbers only.

I’ve worked in rural clinics for 15 years, and I can tell you-this isn’t just theory. Patients are terrified by ‘50% risk reduction’ and refuse meds, then end up in the ER because they didn’t realize their baseline was 1%. I show them pictograms-100 dots, 5 red, 3 green-and suddenly, they get it. It’s not about dumbing down. It’s about humanizing data. We need mandatory visual aids in every prescription discussion. Not optional. Required. Because lives aren’t abstract percentages.

my doctor showed me a little chart with 100 people and colored dots and i finally understood why i was taking the blood pressure med… i think more docs should do this. it’s not hard. just… care.

Oh, so now we’re blaming the pharmaceutical industry for people being too stupid to read? Let me guess-the next thing you’ll say is that people shouldn’t be allowed to drive because they can’t calculate compound interest. This isn’t a crisis of communication. It’s a crisis of personal responsibility. If you’re too lazy to ask for the absolute numbers, don’t blame the system when you get sick. You’re not a victim. You’re a participant.

So… let me get this straight. The same people who think ‘50% reduction’ means they’re now immune to heart attacks are also the ones who believe the moon landing was faked? I mean, we’ve got a whole generation that thinks ‘correlation’ is a brand of yogurt. Is this what happens when we outsource critical thinking to TikTok?

Let me be clear: this isn’t just about stats. It’s about dignity. When you hand someone a pill and say ‘trust me,’ you’re treating them like a child. But when you show them the dots-the real, visual, human numbers-you’re saying: ‘You’re capable of understanding your own body.’ That’s respect. And if your doctor won’t give you that? They’re not your doctor. They’re a sales rep with a stethoscope. Demand the dots. Demand the truth. Your health deserves nothing less.

It’s fascinating how the epistemological dissonance between relative and absolute risk mirrors the broader postmodern fragmentation of truth in late-stage capitalism. The pharmaceutical complex, as a hegemonic apparatus, leverages semiotic inflation-transforming marginal absolute changes into existential narratives via the rhetorical device of relative risk. The lay public, conditioned by algorithmic attention economies, is rendered epistemologically impotent, unable to discern the ontological weight of a 0.09% absolute benefit versus a 90% relative reduction. This isn’t misinformation-it’s structural epistemic violence.

Hey, I used to think this stuff was boring-until my mom had a stroke. Now I make sure every doctor I see shows me the 100-dot chart. Seriously. It’s the only thing that makes sense. If you’re not doing it, try it. It’s like seeing a movie instead of reading a review.

Okay, so here’s the thing-I’ve been thinking about this for like, three days now, and I think it’s deeper than just stats. Like, what if the whole problem is that we’ve turned medicine into a transactional experience? Like, we don’t want to sit with uncertainty anymore. We want a pill that fixes everything, and if it doesn’t, we blame the drug, not our lifestyle, not our genes, not the fact that we eat junk food and sit all day. The relative risk thing? It’s just the symptom. The disease is our collective refusal to accept that health is messy, and sometimes, the best thing you can do is just… walk more. Eat better. Sleep. But that’s not marketable. So we get this whole elaborate theater of percentages and ‘reductions’ and ‘miracle drugs’-and we lap it up like it’s the latest iPhone. We’re not being misled. We’re choosing to be misled. Because the truth is hard. And the lie? It’s shiny. And it comes in a little bottle.

Why do people even need to know this? Just take the pill. If it makes you feel better, it works. If it doesn’t, stop. Who cares about percentages? You’re overthinking it.

Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse in India, and I see this every day-patients scared by ‘90% risk reduction’ ads, then refusing meds because they think side effects are ‘guaranteed.’ I print out simple 100-dot sheets and use them with every patient. No jargon. Just dots. And guess what? They understand. They feel empowered. Not scared. Not confused. Just informed. This isn’t just about medicine. It’s about dignity. We can do better. We must.