Most people think of MRSA as a hospital problem - something that happens to patients after surgery or during a long stay. But if you’ve ever had a red, swollen bump on your skin that turned into a painful abscess, and your doctor said, "It’s MRSA," you might have been shocked. You didn’t go to the hospital. You didn’t have a catheter. You didn’t even take antibiotics recently. So how did you get it?

The truth is, MRSA isn’t just a hospital bug anymore. It’s in gyms, prisons, locker rooms, and even homes. And the line between what’s "community" and what’s "hospital" is disappearing fast.

What Exactly Is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. That’s a mouthful, but here’s the simple version: it’s a type of staph bacteria that doesn’t respond to common antibiotics like penicillin, amoxicillin, or methicillin. Staph bacteria live on the skin of about 30% of healthy people without causing harm. But when they get into a cut, scrape, or wound - especially in places where skin touches skin or shared surfaces - they can cause infections.

MRSA first showed up in hospitals in the 1960s, right after methicillin was introduced. Doctors thought they had staph under control - until the bacteria evolved. Over time, two main types emerged: one that thrives in hospitals (HA-MRSA) and one that spreads in the community (CA-MRSA). But today, those lines are blurring.

Community MRSA: The Bug You Didn’t Expect

Community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) hits people who haven’t been in a hospital in the past year. No surgeries. No dialysis. No catheters. Just everyday life. It’s often seen as a nasty skin infection - a boil, abscess, or pimple that won’t go away. It’s red, hot, swollen, and sometimes oozes pus. In rare cases, it can turn into pneumonia or blood infections, especially in young, healthy people.

What makes CA-MRSA dangerous isn’t just that it’s resistant - it’s that it’s aggressive. Many strains carry a toxin called Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). This toxin kills white blood cells, which are your body’s first line of defense. That’s why CA-MRSA can turn a small bump into a deep, painful abscess in just a day or two.

The most common strain in the U.S. is called USA300. It’s responsible for about 70% of all community cases. It spreads through skin-to-skin contact, shared towels, gym equipment, or even dirty bedding. High-risk places include:

- Prisons - 14.9 times higher risk

- Military barracks - 12.3 times higher risk

- Homeless shelters - 8.7 times higher risk

- Subsidized housing - 6.2 times higher risk

Injecting drug users are also a major source. Needle sharing, poor hygiene, and frequent skin punctures make it easy for USA300 to spread. And once it’s in the community, it doesn’t stay there.

Hospital MRSA: The Resistant Strain

Hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) is different. It’s the kind you’d expect to find in ICUs, surgical wards, or long-term care facilities. These strains carry larger genetic fragments called SCCmec types I-III, which give them resistance to a wide range of antibiotics - not just penicillin, but also erythromycin, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones.

That’s why HA-MRSA infections are harder to treat. Patients often have weakened immune systems, open wounds, IV lines, or breathing tubes - perfect entry points. Infections can turn into bloodstream infections, pneumonia, or surgical site infections. Hospital stays for HA-MRSA patients average over 21 days - more than seven times longer than for CA-MRSA patients.

But here’s the twist: HA-MRSA is losing ground. Studies from Canada and China show that more than 25% of hospital MRSA cases are now caused by strains that originally came from the community. These strains have picked up hospital-level resistance while keeping their aggressive, toxin-producing nature. They’re hybrids - the worst of both worlds.

The Blurring Line: How MRSA Moves Between Settings

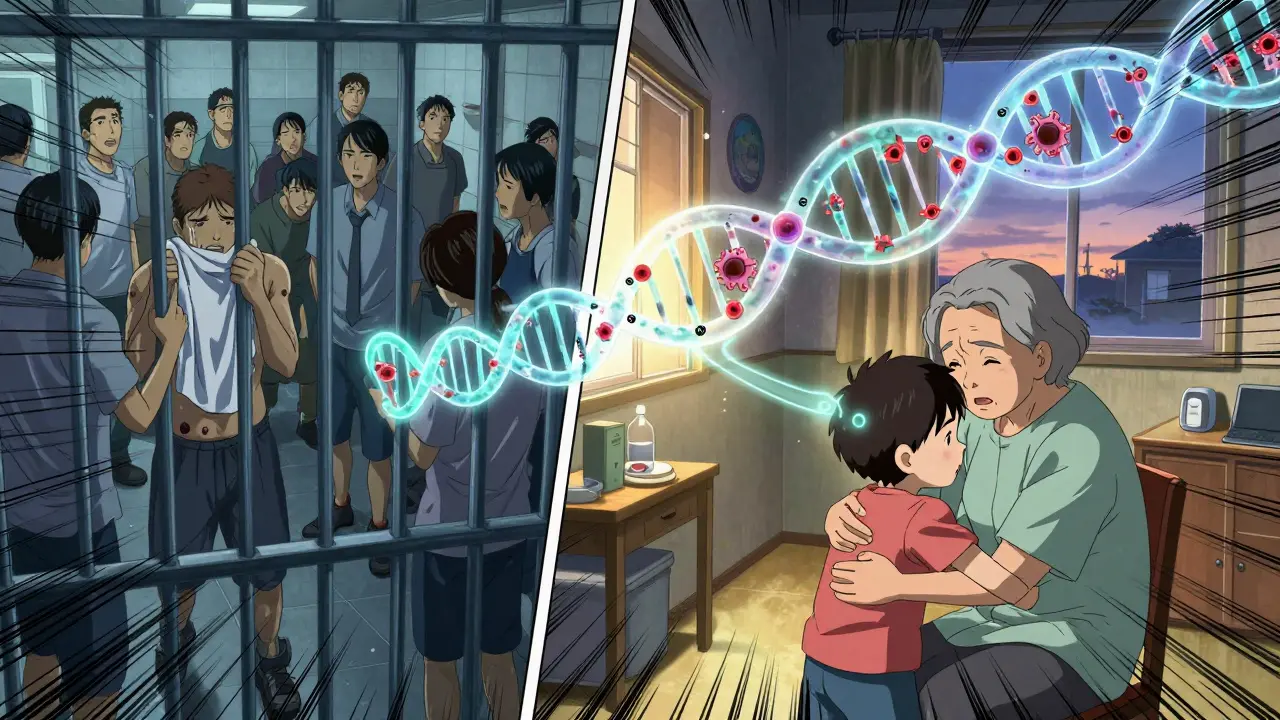

It’s not just patients bringing MRSA into hospitals. Nurses, doctors, and visitors can carry it on their skin or clothes. A person with a mild skin infection from the community might go to the ER, get admitted for observation, and unknowingly introduce CA-MRSA into the hospital.

And it works the other way too. A patient with HA-MRSA gets discharged after a long hospital stay. They’re still colonized - meaning the bacteria is living on their skin, even if they feel fine. They go home, hug their grandkids, share a towel, or touch the doorknob - and now their family has MRSA.

A Canadian study found that 27.6% of hospital-onset MRSA infections were caused by community strains. That’s not a small number. It’s nearly one in three. Meanwhile, 27.5% of community cases came from hospital strains. This isn’t a one-way street - it’s a loop.

Why does this matter? Because infection control in hospitals has always focused on isolating patients with known MRSA. But if the bug is coming from people who don’t even know they have it, those protocols are falling apart.

Treatment: What Works for Which Strain?

Don’t assume all MRSA infections need the same treatment. The approach depends on where it came from - and what it’s capable of.

For CA-MRSA: Many skin infections respond to just one thing - drainage. If you have a large boil, your doctor will cut it open, drain the pus, and clean it out. That’s often enough. If antibiotics are needed, options include:

- Clindamycin - 96% effective against CA-MRSA

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) - 92% effective

- Tetracyclines (like doxycycline) - 89% effective

These drugs work because CA-MRSA hasn’t picked up resistance to them yet. But if you’ve been in a hospital recently, or you’ve taken multiple antibiotics in the past year, your strain might already be resistant.

For HA-MRSA: You’ll likely need stronger drugs because the bacteria resist more types of antibiotics. Vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin, or telavancin are often used. These are powerful, sometimes toxic, and usually given intravenously. They’re not something you take at home.

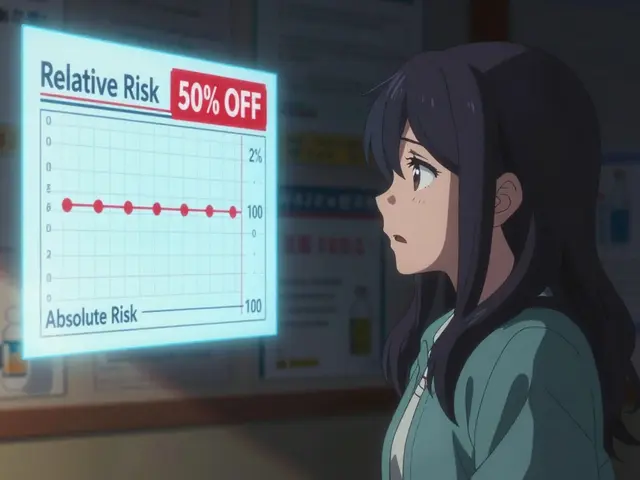

The big problem now? Hybrid strains. They look like CA-MRSA - causing skin infections - but they resist the antibiotics that normally work. That means doctors can’t just guess anymore. They need to test the bacteria in the lab to know which drug will work. Waiting for results can delay treatment. And in severe cases, every hour counts.

Prevention: Breaking the Chain

There’s no magic bullet. But you can stop MRSA from spreading - whether you’re in a hospital, gym, or home.

- Wash your hands often - especially after touching wounds, using the bathroom, or being in crowded places.

- Keep cuts and scrapes covered with clean bandages until healed.

- Don’t share towels, razors, or athletic equipment.

- Shower immediately after working out - don’t sit on gym benches in your sweaty clothes.

- If you’re in a hospital, ask staff to wash their hands before touching you.

- If you’ve had MRSA before, tell your doctor before any procedure - even a simple tooth extraction.

Hospitals are starting to screen high-risk patients - like those coming from prisons or nursing homes - for MRSA before admission. Some use special soaps to reduce skin colonization. But without better tracking of community strains, these efforts are like putting a bandage on a leaky dam.

The Future: One System, Not Two

Doctors and researchers now agree: the old labels - "community" and "hospital" - are outdated. MRSA moves. It evolves. It adapts. The real threat isn’t one strain or the other - it’s the system that treats them as separate.

We need surveillance that tracks MRSA across the whole chain: from the homeless shelter to the ER to the ICU to the family home. We need labs that test not just for resistance, but for toxin genes like PVL. We need antibiotics used smarter - not as a first response for every pimple.

And most of all, we need to stop thinking of MRSA as something that happens to "other people." It’s in your gym bag. It’s on your kid’s locker. It’s in the hospital next door. And if you ignore it, it will find you.

Can you get MRSA from a toilet seat?

It’s possible, but unlikely. MRSA spreads mostly through direct skin contact or contact with contaminated surfaces like towels, razors, or gym equipment. Toilet seats aren’t a major source because the bacteria don’t survive long on dry, non-porous surfaces. Focus on hygiene after touching shared items - not the toilet.

Is MRSA contagious?

Yes. MRSA spreads through direct skin contact or by touching objects contaminated with the bacteria. You can carry it on your skin without symptoms and still pass it to others. That’s why covering wounds and washing hands are so important - even if you feel fine.

Can MRSA go away on its own?

Small skin infections sometimes drain and heal without antibiotics, especially if you keep the area clean and covered. But never assume it’s gone. Untreated MRSA can spread deeper into tissue, enter the bloodstream, or turn into pneumonia. Always get it checked by a doctor.

Does hand sanitizer kill MRSA?

Alcohol-based hand sanitizers (at least 60% alcohol) can reduce MRSA on skin, but they’re not as reliable as soap and water - especially if your hands are visibly dirty or greasy. For MRSA prevention, washing with soap and water for 20 seconds is still the gold standard.

If I’ve had MRSA once, will I always have it?

Not necessarily. Many people clear MRSA from their skin after treatment. But some remain colonized - meaning the bacteria lives on them without causing illness. This can last for months or even years. If you’ve had MRSA before, you’re at higher risk of getting it again, especially if you’re exposed to the same environments.

Comments

mrsa in gyms? lol i got a boil from my dumbass roommate using my towel and now im the bad guy. no one cares about hygiene until its on them.

i just want to say thank you for writing this. i had mrsa twice and no one ever told me how it spreads. i thought it was just from hospitals. now i tell my kids to shower after practice and never share shoes. you saved my family from more panic.

this is why we need borders closed and immigration checked. these strains come from places where people dont wash their hands. its not the gym its the outsiders bringing it in

you know what they dont tell you? the government knows this is spreading faster than they admit. they keep calling it community vs hospital to avoid panic. its all connected. theyre lying to you.

obviously this is all a big pharma scam. they want you to think you need expensive antibiotics. drain it with a needle and put honey on it like your grandma did. the system wants you dependent. dont trust the doctors. theyre paid to lie.

i had mrsa last year and my doc gave me bactrim but i forgot to take it all so it came back. now i think its in my walls. my dog sneezes funny sometimes. maybe its in the air?

this is just capitalism’s final stage. we turned health into a product. mrsa thrives because we dont care about the poor. prisons are labs. shelters are breeding grounds. the rich get vancomycin. the rest get a bandaid and a prayer.

It is imperative that we recognize the moral responsibility inherent in public health infrastructure. The normalization of poor hygiene practices in communal environments reflects a broader societal decay in personal accountability. Without systemic reform and rigorous education, we are not merely treating infections-we are enabling a culture of neglect that endangers us all.

i think the real question is not whether mrsa is community or hospital-but why we keep treating it like two separate problems. we’re all connected. your gym towel touches your kid’s backpack. your cousin’s hospital stay touches your neighbor’s door handle. maybe the answer isn’t better drugs-it’s better awareness. wash your hands. cover your cuts. don’t be embarrassed to ask if someone’s been sick. it’s not weird. it’s human.