Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC is a high‑grade form of breast cancer that lacks estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors) accounts for about 10‑15% of all breast cancers but behaves very differently from other subtypes. If you or a loved one has just heard the term, you probably wonder what makes it unique, why it appears, and how doctors treat it. This guide walks through the biology, risk factors, warning signs, and the most current treatment options so you can make sense of the medical jargon and feel a bit more in control.

Key Takeaways

- TNBC does not express ER, PR, or HER2 receptors, which limits hormone‑based therapies.

- Genetic mutations (especially BRCA1/2), younger age, and certain ethnic backgrounds increase risk.

- Common symptoms include a new lump, skin changes, or nipple discharge; early detection improves outcomes.

- Standard care mixes surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation; newer options include immunotherapy and PARP inhibitors.

- Participating in clinical trials can give access to cutting‑edge treatments.

What Makes Triple‑Negative Breast Cancer Different?

Breast cancer is classified by the presence or absence of three receptors:

- Estrogen Receptor (ER)

- Progesterone Receptor (PR)

- Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)

When all three are missing, the tumor is called "triple‑negative". Because hormone‑blocking drugs (like tamoxifen) and HER2‑targeted agents (like trastuzumab) rely on those receptors, they are ineffective against TNBC. Instead, treatment leans heavily on chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation, with newer therapies aiming at the tumor’s DNA repair pathways or immune environment.

Common Causes and Risk Factors

Most breast cancers don’t have a single cause, but several factors raise the odds of developing TNBC:

- Genetic mutations: Inherited changes in BRCA1 or BRCA2 dramatically increase TNBC risk, especially for women under 40.

- Age: Although breast cancer overall peaks after menopause, TNBC is more common in women younger than 50.

- Ethnicity: African‑American and Hispanic women have higher incidence rates than non‑Hispanic whites.

- Reproductive history: Early menarche, late menopause, and not having children or breastfeeding can contribute.

- Lifestyle: Obesity, especially abdominal fat, and heavy alcohol consumption modestly raise risk.

Researchers also note that certain environmental exposures-like ionizing radiation-might play a role, though evidence is still emerging.

How Does TNBC Present? Symptoms to Watch For

Symptoms often mirror those of other breast cancers, but catching them early matters because TNBC tends to grow quickly. Look out for:

- A painless, firm lump that feels different from surrounding tissue.

- Skin dimpling or a dimpled appearance (resembling an orange peel).

- Redness, swelling, or a rash on the breast or chest wall.

- Nipple changes - inversion, crusting, or discharge that isn’t milk.

- Unexplained pain or tenderness in the breast or armpit.

If any of these signs appear, schedule a diagnostic mammogram or breast ultrasound promptly. Early imaging can reveal a tumor before it spreads to nearby lymph nodes, which is crucial for a better prognosis.

Diagnosis: From Imaging to Molecular Profiling

Once a suspicious area is found, doctors follow a stepped approach:

- Imaging: A digital mammogram, often supplemented by an ultrasound, provides size and shape details.

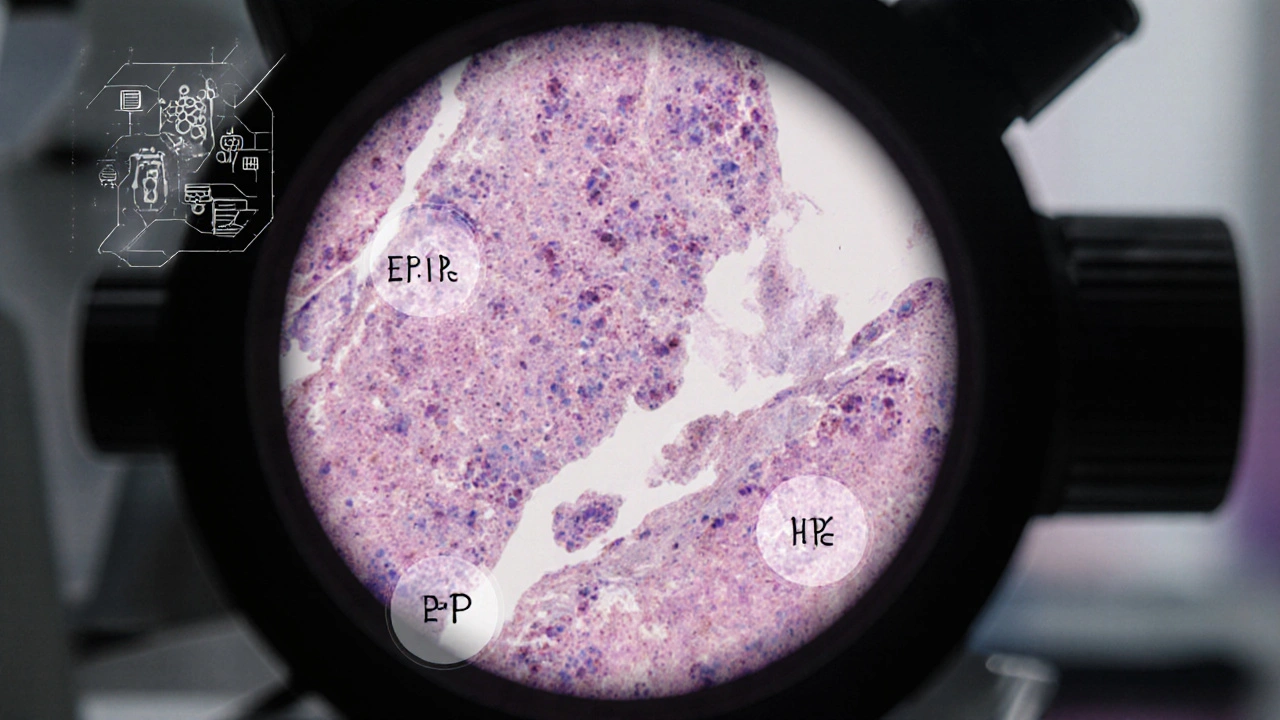

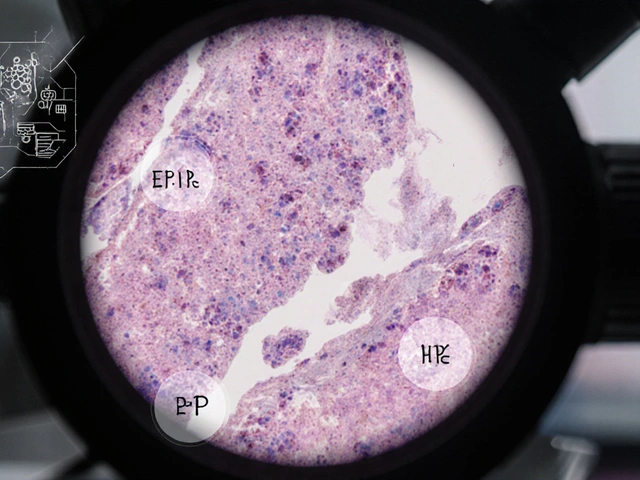

- Biopsy: A core‑needle sample is examined under a microscope. Pathologists assess tumor grade, Ki‑67 proliferation index, and, critically, receptor status (ER, PR, HER2).

- Genetic testing: If the patient is under 50, has a family history, or the tumor shows BRCA‑related features, testing for BRCA1/2 and other DNA‑repair genes is recommended.

- Staging: Using the TNM system (Tumor size, Node involvement, Metastasis), clinicians determine how far the disease has progressed.

All these data points guide treatment planning and help estimate survival odds.

Standard Treatment Options

Because TNBC doesn’t respond to hormone or HER2 therapies, the backbone of care is a multimodal strategy:

- Surgery: Either a lumpectomy (breast‑conserving) or mastectomy removes the primary tumor. Choice depends on tumor size, location, and patient preference.

- Radiation: After breast‑conserving surgery, whole‑breast radiation reduces local recurrence. Even after mastectomy, radiation may be used if many lymph nodes are involved.

- Chemotherapy: Usually given before surgery (neoadjuvant) to shrink the tumor and assess response. Common regimens include anthracyclines (doxorubicin) plus taxanes (paclitaxel). A pathologic complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant chemo strongly predicts long‑term survival.

While traditional chemo remains effective for many patients, the high recurrence rate in TNBC has spurred the development of newer agents.

Emerging Therapies: Immunotherapy and Targeted Drugs

In the last few years, two classes have changed the treatment landscape:

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Drugs like atezolizumab (anti‑PD‑L1) combined with nab‑paclitaxel have shown improved progression‑free survival in metastatic TNBC that expresses PD‑L1.

- PARP inhibitors: For patients with germline BRCA mutations, agents such as olaparib or talazoparib exploit the tumor’s defective DNA repair, leading to cell death.

Clinical trials are also testing antibody‑drug conjugates (ADCs) that deliver chemotherapy directly to tumor cells, and agents targeting the androgen receptor, which is present in a subset of TNBC.

Choosing the Right Approach: Factors That Matter

Deciding which therapies to use isn’t one‑size‑fits‑all. Doctors weigh several variables:

- Stage at diagnosis: Early‑stage disease usually starts with surgery and radiation, while metastatic cases prioritize systemic therapy.

- Genetic profile: BRCA‑positive patients may get PARP inhibitors earlier.

- PD‑L1 status: Determines eligibility for immunotherapy.

- Patient health: Age, heart function, and co‑existing conditions influence chemo tolerance.

- Personal preferences: Desire to preserve the breast, willingness to enroll in trials, etc.

Having a multidisciplinary team-oncologist, surgeon, radiologist, and genetic counselor-helps tailor the plan.

Comparison: TNBC vs Hormone‑Positive Breast Cancer

| Feature | Triple‑Negative (TNBC) | Hormone‑Positive (ER/PR+) |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Status | ER‑, PR‑, HER2‑ | ER+, PR+, HER2‑/+ |

| Typical Age at Diagnosis | 30‑50 years | 50‑70 years |

| Common Ethnic Risk | African‑American, Hispanic | Non‑Hispanic white |

| Prognosis (5‑year survival) | ~70% (early stage) | ~90% (early stage) |

| Standard Systemic Therapy | Chemotherapy ± Immunotherapy | Endocrine therapy (tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors) |

| Targeted Options | PARP inhibitors (BRCA‑mut), PD‑L1 blockers | CDK4/6 inhibitors, HER2‑targeted therapy (if HER2+) |

Living With TNBC: Support, Lifestyle, and Follow‑Up

Medical treatment is just one piece of the puzzle. Survivors report that daily habits, mental health, and community resources matter a lot.

- Regular follow‑up: After completing primary therapy, imaging (annual mammogram or MRI) and physical exams every 3‑6 months for the first two years are standard.

- Exercise: Moderate activity (150 minutes per week) lowers recurrence risk and improves fatigue.

- Nutrition: A plant‑forward diet rich in fiber, lean protein, and omega‑3 fatty acids supports immune function.

- Mental health: Counseling, support groups, or peer‑to‑peer networks help manage anxiety and depression that often accompany a cancer diagnosis.

- Clinical trials: Checking ClinicalTrials.gov or discussing with your oncologist can provide access to cutting‑edge therapies.

Families can also benefit from genetic counseling if a BRCA mutation is found, as relatives may need testing and preventive strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is triple‑negative breast cancer curable?

When caught early and treated with surgery, radiation, and effective chemotherapy, many patients achieve long‑term remission. However, TNBC has a higher chance of recurrence than hormone‑positive cancers, so close monitoring remains essential.

Can men get triple‑negative breast cancer?

Yes, although male breast cancer is rare (about 1% of all breast cancers). When it occurs, it can be triple‑negative, and treatment follows similar principles as in women.

What is a pathologic complete response (pCR) and why does it matter?

pCR means that after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, no invasive cancer is found in the breast or lymph nodes at surgery. In TNBC, achieving pCR is linked to a significantly lower risk of distant recurrence.

Are there lifestyle changes that can lower my TNBC risk?

Maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol, staying physically active, and breastfeeding (when possible) are associated with modest risk reductions. However, genetics remain a strong driver for TNBC.

How do doctors decide if I should get immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy is typically offered for metastatic TNBC that tests positive for PD‑L1 on tumor‑infiltrating immune cells. A pathology report will indicate PD‑L1 status, guiding eligibility.

Bottom Line

Triple‑negative breast cancer is aggressive but not unbeatable. Understanding its biology, recognizing symptoms early, and staying informed about evolving treatments give patients the best chance for favorable outcomes. If you or someone you know is facing a TNBC diagnosis, partner with a knowledgeable oncology team, consider genetic testing, and explore clinical trial opportunities-knowledge truly powers hope.

Comments

Alright, let’s tear this TNBC thing apart like a lab rat on a hot plate. First off, triple‑negative isn’t just a fancy label – it’s the cancer equivalent of a rogue ninja that refuses to bow to hormonal weapons. No ER, no PR, no HER2 – you’ve basically stripped the tumor of its shiny armor, leaving it to fight with raw brute force, which means chemo becomes the only sword in the arsenal. The genetic backdrop is a wild ride, especially when BRCA1/2 are lurking in the background like hidden landmines, turning otherwise average risk into a ticking time‑bomb for women under 40. Ethnicity slides into the mix too; African‑American and Hispanic women see higher incidence, a sobering reminder that biology and sociocultural factors dance a twisted tango.

Now, let’s talk symptoms – a painless lump that feels like a stubborn pea, skin that looks orange‑peelled, or a rash that screams “I’m not normal”. These signs whisper before they shout, so early imaging is the secret handshake to catch the beast before it spreads its claws. Imaging and biopsies give the cold, hard facts: the Ki‑67 index, the grade, the dreaded triple‑negative status. Once those numbers land, treatment hops onto a multi‑pronged carousel – lumpectomy or mastectomy, radiation, and a chemo cocktail that would make a veteran chemist blush.

But here’s the kicker: the tumor doesn’t like being boxed in, so the new kids on the block – checkpoint inhibitors like atezolizumab and PARP inhibitors such as olaparib – stride onto the stage, targeting DNA repair flaws and the immune evasion tricks the cancer uses. Clinical trials are the wild west, offering access to ADCs and androgen‑receptor blockers that might just be the next big bang.

Survival stats? Early‑stage TNBC can still pull a ~70% five‑year survival, but that drops like a stone if the disease spreads. The mantra for patients is simple: stay vigilant, get those scans every few months, keep moving, and eat clean – plant‑forward meals and omega‑3s are like armor for your immune system. Family members should consider genetic counseling because a BRCA mutation isn’t just a personal issue; it’s a family saga.

Bottom line – TNBC is aggressive, unpredictable, and unforgiving, but it isn’t invincible. Arm yourself with knowledge, push for the newest therapies, and never stop asking your oncologist about trial options. The battle is fierce, but with the right weapons and a relentless spirit, you can tip the scales in your favor.

Truth is, the soul of medicine hides in the paradox of hope and dread, a dance we all know too well. Your rundown captures it, but the deeper why‑not‑us question still lingers.

Whoa, you just opened a can of philosophical worms 😜

Hey folks, if you or someone you know is dealing with TNBC, remember you’re not alone – lean on support groups, stay active, and keep those doctors in the loop. Small steps every day can make a huge difference!

The information is accurate, but please avoid using slang when discussing medical facts; clarity is essential for readers seeking reliable guidance.

Sending a big virtual hug to everyone fighting this battle 💪❤️. Stay strong, stay informed, and don’t hesitate to ask your care team about the latest clinical trials – they might hold the key to a brighter tomorrow!

In the grand tapestry of existence, confronting a diagnosis like TNBC is a reminder that uncertainty is the only certainty; yet within that uncertainty lies the seed of resilience 🌱.

Just to break it down: TNBC lacks three common receptors, so hormone therapies won’t work. Doctors rely on surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, plus newer options like immunotherapy for those who qualify. If you have a BRCA mutation, ask about PARP inhibitors. Regular follow‑ups and a healthy lifestyle can help reduce recurrence risk.

Great summary! I’d add that joining a clinical trial can give access to cutting‑edge treatments, and many patients find that the community support they get during trials boosts morale. Also, keep an eye on PD‑L1 testing – it can open doors to immunotherapy options.