When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy and it’s not the brand-name drug you expected, there’s a good chance it’s a generic. But how did that generic drug get approved to be sold in the U.S.? The answer lies in something called an ANDA - Abbreviated New Drug Application. It’s the secret weapon behind why generic drugs are so common and so much cheaper than brand-name versions.

What Exactly Is an ANDA?

An ANDA is a formal request submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to get approval to sell a generic version of a drug that’s already on the market. It’s called “abbreviated” because it doesn’t require the same long, expensive clinical trials that brand-name drugs go through. Instead, the company making the generic just needs to prove their version works the same way as the original.

The system was created in 1984 by the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, generic manufacturers had to start from scratch - running full clinical trials even though the original drug’s safety and effectiveness were already proven. That made it nearly impossible for generics to compete. The Hatch-Waxman Act changed that. It gave generic drug makers a clear, faster path to market by letting them rely on the FDA’s existing data from the brand-name drug.

How Does an ANDA Work?

To get approval, a generic drug must meet strict criteria:

- It must have the same active ingredient as the brand-name drug.

- The dosage form (pill, injection, cream, etc.) must be identical.

- The strength (amount of active ingredient) must match exactly.

- The way it’s taken (oral, topical, injected) must be the same.

- The intended use (what it treats) must be identical.

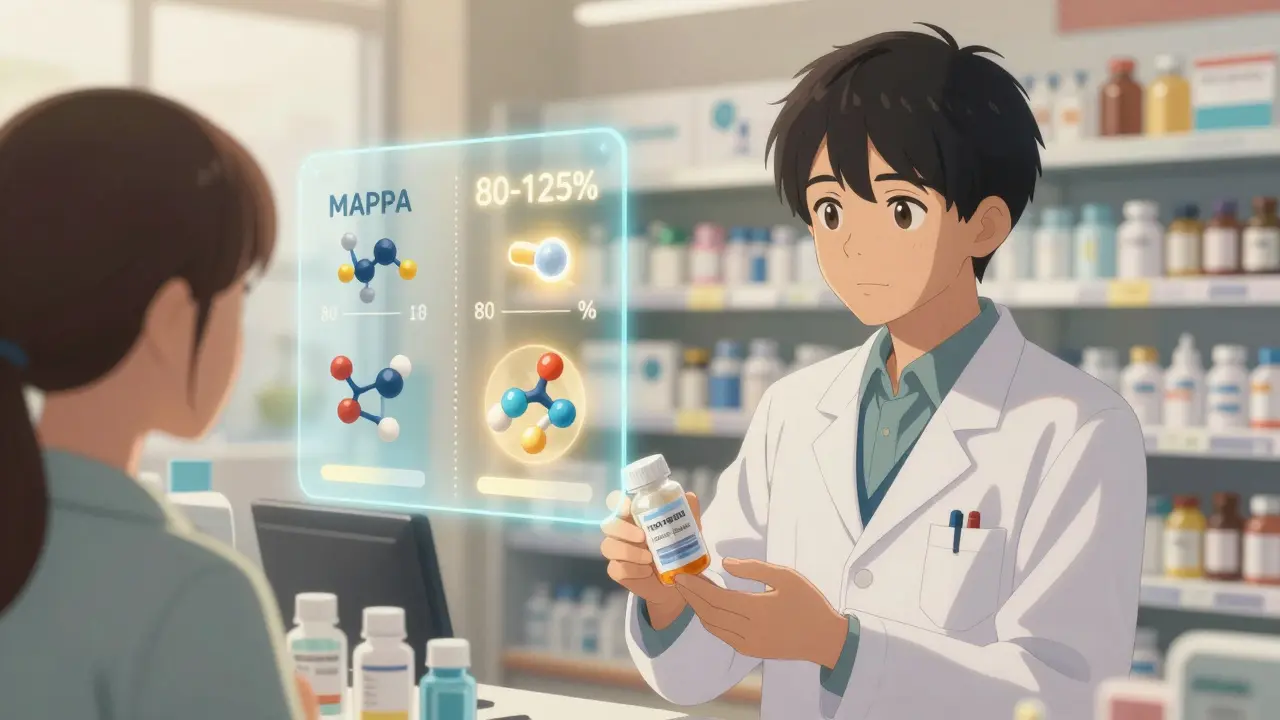

That’s not all. The generic must also prove it’s bioequivalent. That means your body absorbs it at the same rate and to the same extent as the brand-name drug. This is tested in small studies with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Researchers measure how much of the drug enters the bloodstream over time - looking at two key numbers: how much total drug is absorbed (AUC) and how fast it peaks (Cmax). For approval, the generic’s results must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s numbers. That’s a tight window, and it ensures there’s no meaningful difference in how the drug works in your body.

Minor differences are allowed - like different fillers, colors, or packaging - as long as they don’t affect how the drug works. You might notice a generic pill looks different from the brand, but that’s just because of inactive ingredients, not the medicine itself.

ANDA vs. NDA: The Big Difference

Every new brand-name drug goes through a New Drug Application (NDA). That’s a massive undertaking. It usually takes 10 to 15 years and costs over $2 billion. It includes years of lab research, animal testing, and multiple phases of human trials to prove the drug is safe and effective.

An ANDA skips all that. Instead of building the evidence from scratch, it leans on the data already approved by the FDA. That’s why an ANDA typically takes only 3 to 4 years to develop and costs between $1 million and $5 million. The FDA’s review time for a standard ANDA is 10 months under current rules, thanks to the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). That’s the same as a priority NDA - which means generics aren’t treated like second-class citizens. They’re held to the same standard, just with a smarter process.

Why Does This Matter?

Because of ANDAs, over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. But here’s the kicker: generics make up only about 23% of total drug spending. That’s a massive savings. In 2023 alone, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $313 billion. That’s money in people’s pockets - not just for patients, but for insurers, Medicare, Medicaid, and employers.

Take Humira, for example. When its patent expired, 12 different generic versions hit the market within a year. Prices dropped by more than 80%. That’s the power of ANDAs in action.

And it’s not just about cost. It’s about access. For people managing chronic conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, or depression, affordable generics mean they can stick with their treatment. Without the ANDA pathway, millions would be forced to skip doses or go without.

Who Uses the ANDA Pathway?

It’s not just small companies. The big players - Teva, Viatris, Sandoz - all rely on ANDAs. But smaller manufacturers use it too. The system was designed to open the door for competition. And it worked. Today, over 11,000 generic drugs have been approved through ANDAs. That’s more than any other approval route in U.S. history.

Companies that have dedicated regulatory teams - people who know the FDA’s guidelines inside and out - have a much better shot at getting approved on the first try. In fact, those with specialized teams see first-cycle approval rates of 42%, compared to just 28% for those without. Why? Because ANDA submissions are detailed. They need data on manufacturing, quality control, stability testing, and labeling. One missing piece, and the FDA sends back a “complete response letter” - basically a list of what’s wrong.

What Goes Wrong With ANDAs?

Not every ANDA gets approved right away. The most common reasons for rejection?

- Manufacturing issues (32% of rejections): Inconsistent production, poor quality controls, or unapproved facilities.

- Inadequate bioequivalence data (27%): Studies that don’t meet the 80-125% range, or flawed study design.

- Patent disputes: If the brand-name company still holds patents, the generic maker must certify against them. If they challenge a patent, the FDA can delay approval for up to 30 months while lawsuits play out.

Some drugs are harder to copy than others. Complex generics - like inhalers, topical creams, or injectables with special delivery systems - are tricky. Standard bioequivalence tests don’t always work. The FDA has been working on new guidance for these since 2022, but they still take longer to approve. That’s why most generics today are still simple oral pills.

The Future of ANDAs

The FDA is pushing to improve the process. Under GDUFA IV (2023), the goal is to get 90% of ANDAs approved on the first try by 2027. Right now, it’s around 65%. That’s a big jump, but it’s doable with better guidance and more resources.

Also, more complex generics are coming. By 2028, experts predict that 25% of the generic market will be made up of drugs that are harder to copy - things like nasal sprays and transdermal patches. That means ANDAs will evolve, too. The FDA is already creating specific pathways for these.

But there’s a risk. Most generic drug ingredients are made in just a few countries - India and China. If supply chains break down, shortages happen. That’s why regulators are now looking at diversifying manufacturing sources. It’s not about stopping ANDAs - it’s about making them more resilient.

Final Thoughts

The ANDA isn’t a loophole. It’s a smart, science-backed system that saves lives and money. It lets us keep using proven medicines without paying brand-name prices. It’s why you can get a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril for under $5. It’s why people with diabetes can afford insulin. It’s why millions of Americans don’t have to choose between their medication and their rent.

Behind every generic pill you take, there’s a carefully built ANDA. And that system - born from a 1984 law - is one of the most successful public health policies ever written.

Is an ANDA the same as a patent expiration?

No. A patent expiration means the brand-name company no longer has exclusive rights to sell the drug. An ANDA is the formal application a generic company submits to the FDA to get approval to sell that drug. A generic company can file an ANDA before a patent expires, but the FDA won’t approve it until the patent is gone - unless the generic challenges the patent and wins in court.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and performance as brand-name drugs. Studies show that 97% of generic drugs are therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. Millions of people use generics every day without issue. The FDA monitors adverse events for both brand and generic drugs equally.

Why do generic pills look different?

U.S. law requires generic drugs to look different from brand-name versions to avoid trademark infringement. That means the color, shape, or size might change - but the active ingredient and how it works in your body are identical. The differences are purely cosmetic and don’t affect safety or effectiveness.

Can any company submit an ANDA?

Any company can submit an ANDA, but it requires serious expertise. The submission must include detailed data on chemistry, manufacturing, controls, and bioequivalence. Most companies hire regulatory specialists or partner with contract research organizations to get it right. The FDA doesn’t accept incomplete or poorly prepared applications.

How long does it take to get an ANDA approved?

Under current FDA rules, a standard ANDA review takes about 10 months. But the whole process - from starting development to final approval - usually takes 3 to 4 years. This includes formulating the drug, running bioequivalence studies, setting up manufacturing, and submitting the application. If the FDA requests more data, it can take longer.

Comments

Let me tell you something - this ANDA system is basically the reason I’m still alive. My dad had heart failure, and back in 2010, his brand-name meds were costing $400 a month. Four hundred. For a guy on Social Security. Then generics hit. Suddenly, it was $12. Not $120. $12. I cried. Not because I was sad - because I realized the system actually worked. The FDA didn’t cut corners. They just stopped letting pharma companies charge a mortgage on a pill. And yeah, I know some people say ‘but what about quality?’ - I’ve been on generic lisinopril for 12 years. My BP is stable. My kidneys are fine. And I haven’t turned into a lizard. So stop worrying about the color of the pill and start worrying about people who can’t afford to breathe.

Man, I love how this post breaks it down. I work in pharma logistics in Sydney, and I see the supply chain side of this every day. What most folks don’t realize is that the real magic isn’t just the science - it’s the paperwork. Someone, somewhere, has spent 18 months filling out 800 pages of CMC data (chemistry, manufacturing, controls) just so your generic metoprolol doesn’t dissolve into a puddle in your stomach. And if one batch of lactose is 0.3% off? The whole thing gets bounced. It’s insane. The FDA’s review team? They’re basically PhDs who’ve memorized the Federal Register like it’s a religious text. And yet, we still act like generics are ‘cheap knockoffs.’ No. They’re the result of a billion hours of meticulous, unglamorous labor. Respect the grind.

so like… wait, so the FDA just lets you copy a drug if you prove it works the same?? no kidding?? that’s wild. i thought you had to do all the animal tests and stuff again. also, why do generics look different?? like, i got a blue pill yesterday and i was like ‘is this the right one??’ turns out it’s just because the brand had a trademarked color?? mind blown. also, i heard somewhere that some generics are made in india - is that safe?? like, i don’t wanna die because my blood pressure med was made in a garage. also, is it true that some companies get approved on the first try?? i thought it took years. also, why do some people say ‘avoid generics’?? are they just trying to sell you the brand name??

Oh wow. A whole article about how the FDA doesn’t let drug companies rip us off? How novel. Next you’ll tell us the sun rises in the east and that people who pay $100 for a 30-day supply of metformin are idiots. Look - I’m not surprised this exists. What shocks me is that it took 40 years for anyone to admit this was a good idea. And yet, here we are - 2025, and people still think generics are ‘inferior.’ You know what’s inferior? Paying $800 for a 30-day supply of a drug that’s been around since 1982. The real scandal isn’t the ANDA - it’s that we let monopolies exist for 20 years just so CEOs can buy yachts. Stop acting like this is a miracle. It’s justice. And it’s long overdue.

Y’all ever notice how everyone gets emotional about generics but no one talks about the people who actually make them? Like, I’ve been to factories in Tamil Nadu and Hyderabad. Thousands of workers - mostly women - in heat, with no AC, packing pills 12 hours a day. They’re not making $15 an hour. They’re making $2.50. And yet, their work is the reason your insulin costs $5. We cheer the system, but we never cheer the people who keep it running. Also - I’ve seen FDA inspectors walk into a facility and spot a tiny crack in a sealant tube from 30 feet away. They’re not just bureaucrats. They’re scientists with laser eyes. And yeah - I’m proud of this system. But let’s not romanticize it. It’s built on sweat. And silence.

Okay, real talk: I’m a nurse. I’ve watched people choose between their meds and their rent. I’ve seen diabetic patients skip doses because they couldn’t afford the brand. Then the generics came. And suddenly? They were alive again. One lady came in last month with her husband - both on generics. She said, ‘We used to fight about who got to take the pill first. Now we can afford to eat together.’ That’s not a policy. That’s a miracle. And it’s not magic. It’s the Hatch-Waxman Act. So next time someone says ‘I only take brand,’ ask them why. Is it science? Or fear? Because if it’s fear - you’re being sold a lie.

Just wanted to say - I’m a pharmacist, and I’ve been doing this for 22 years. I’ve seen generics go from ‘oh no, is this safe?’ to ‘can I get the generic version, please?’ - and honestly? It’s one of the most rewarding things I’ve witnessed. The thing people miss? Bioequivalence isn’t just a number. It’s a promise. When a generic says it’s 80-125% equivalent? That’s not a range - that’s a guarantee. It’s tighter than most consumer products. Your phone charger? Your shampoo? Your cereal? No one tests those like this. But we do this for medicine. And yet, we still treat it like it’s a gamble. It’s not. It’s science. And it’s working. I’ve never seen a patient get worse on a generic. Ever. Not once. So please - stop doubting. Trust the data.

The ANDA pathway is a paradigmatic example of regulatory arbitrage optimized for therapeutic equivalence. By leveraging the reference-listed drug’s (RLD) safety and efficacy database, the sponsor circumvents the need for preclinical and Phase I-III trials, thereby reducing development costs by an order of magnitude. The bioequivalence (BE) requirement - anchored in the 80-125% confidence interval for AUC and Cmax - is statistically robust and validated by FDA’s 2003 BE Guidance. The 10-month review timeline under GDUFA reflects a well-resourced, risk-based inspection regime. That said, the rising prevalence of complex generics (e.g., nasal aerosols, transdermal systems) necessitates novel BE endpoints, such as in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) modeling, which remains underutilized. The real bottleneck? Manufacturing compliance - specifically, deviations from CGMP (current Good Manufacturing Practices) - which accounts for >30% of CRLs. Until supply chains are vertically integrated with real-time quality analytics, the system will remain vulnerable to geopolitical shocks.

This is actually really cool. I never thought about how much work goes into making a generic. I just assumed they were cheaper because they cut corners. But the more I read, the more I realize they’re just smarter. Like - they don’t have to reinvent the wheel. They just have to prove it turns the same way. And that’s actually brilliant. Also, I had no idea that 90% of prescriptions are generics. That’s wild. I guess I just see the brand names on TV ads. Never thought about the quiet heroes behind the scenes. Thanks for explaining this so clearly.

So basically, we’re just letting other countries make our medicine now? Cool.